Det Insp Taylor, who’d pursued Carstens so doggedly, told journalists he believed Carstens’ body count was at least seven.

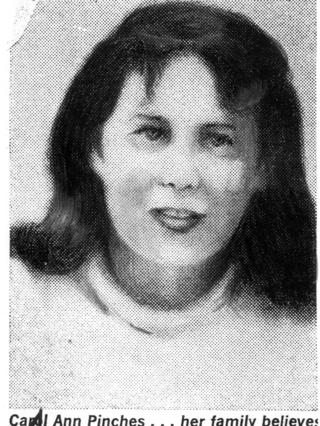

One, 16-year-old Carol Ann Pinches, had been mentioned during the trial.

Carol had been a close friend of Peter Colburn’s and had disappeared from her family’s Riverview QLD home a few days before the young meatworker went missing.

In prison, Carstens had told a detective he knew where she was buried. He later denied mentioning her.

“My mother’s life is a misery,” Carol’s brother told The Courier-Mail three years after she disappeared.

“She has nightmares, gets highly emotional and hysterical. It’s because my sister is missing. She is dead. She has been murdered.”

THE job ad offered a tropical North Queensland adventure on an old pearling lugger called the ‘Cutty Sak’; six months scuba diving work; good pay; with full keep. It all sounded too good to be true ... it was.

IT was hardly the work of a practised artist but it told its story well enough.

A tiny island shaded by a single palm tree. Crude shark fins emerging from the surrounding ocean.

And three crude figures. Stranded.

Sixteen-year-old Peter Colburn, 21-year-old Bruce Peters, and Arlie Rowan’s 18-year-old son Kerry. The artist had drawn them with beards. They’d been there a long time, the picture was seeming to say.

The letter, written on jail paper, had come addressed to the grieving mother.

By then, her boy had been gone for a year. If its contents were true, it meant her Kerry was still alive.

But it had been a long time since anyone had really believed the story about the boat and the dive trip.

The missing youths were drawn in the shade of the island’s only tree. The artist had included a speech bubble for each.

“Dad! Dad!” one was saying.

“Food,” said another. The last said: “Water.”

There was a message too – an offer for a grieving mother.

“Undoubtably you are being misled by the police,” the author wrote.

“Be assured that Kerry will never be turned over to them. The police are only interested in the dramatisation of their situation, which typifies the methods of the Queensland Police...”

The boys were well, it said. But that could change. Their current home was “plagued by malaria, dysentery, typhus, tuberculosis and innumerable other diseases”.

“The only person to get them home is Al.”

Mrs Rowan, the letter writer urged, should push for the release of “Al”.

If Al was not released by June 18, 1971, the trio would be put ashore on one of the 6000 islands that made up the Indonesian and Philippines groups.

“As you know, they are very remote,” the author warned.

“It is beyond my comprehension how some parents can act so casual over the welfare of their own flesh and blood.”

It was a clumsy act of manipulation. But it wouldn’t work. Everybody knew the boys were already dead.

Police were not about to fall for one of Alexander Carstens tricks. And there would be many of them.

THE ADVERTISEMENT appeared on April 15, 1970. And by then, Peter Colburn was already dead.

Alexander Carstens was a 28-year-old meatworker with a wife and four children who had the good fortune to be living apart from him.

He’d tried his hand at labouring and driving trucks, but in 1970, he was working at the Dinmore Meatworks with young Peter.

His home was a small flat on Highfield St, Oxley.

Peter lived in his own flat in Ipswich. He shared the unit with a local sawmill operator and on weekends would stay with his parents at their dairy farm nearby.

In March, 1970, Peter came home with a cut above his eye. His clothes were dirty and dishevelled, as though he’d been in a fight.

And that was exactly what had happened, Peter told his flatmate when questioned.

He’d got into a fight with a man at work. He didn’t say who and the flatmate didn’t push.

A few days later, on Friday, March 13, Peter went to work and didn’t come home.

He’d left that night at 7.12pm with Carstens.

Carstens would later claim he dropped Peter back to Ipswich. But nobody saw him arrive home.

His clothes were still at home. His bank account, which held $600, remained untouched.

Nobody worried at first. Peter had mentioned a weekend shooting trip.

By Wednesday, friends were concerned enough to contact the Colburns.

Wallace Colburn went to visit Carstens the next day.

Mr Colburn knew his son idolised Carstens. The pair were friends. His son had talked about Carstens teaching him to scuba dive.

“We were like brothers,” Carstens told the older man.

“We eat each other’s bread. If he comes back, I’ll take half a day off to fetch him home.”

He told Mr Colburn he didn’t know where Peter had gone. But later he’d change his story.

Peter was on a boat off North Queensland, he explained. He got a job as a skindiver. Carstens didn’t know when he’d be back.

The story seemed strange. Peter had not mentioned a new job. He’d left no note. He hadn’t told his bosses at the meatworks.

The ad went in the paper in April.

“Men and boys wanted. Young scuba divers. Six months’ work in north Queensland. Must have own tanks. Good wages. Full keep. Inquire by letter only to Mr Alex, c/- boning room, meatworks, Dinmore,” it read.

Police believe the newspaper advertisement was part of Carstens’ plot to give weight to the story he’d told Peter’s parents.

There was a diving expedition, he’d insist. Peter had gone to sea on an old pearling lugger called the Cutty Sak. She was 60ft long and off white with a yellow trim. At least that’s what he told those who answered his ad.

But in reality, the Cutty Sak did not exist.

Bruce Peters was the next to disappear. The 22-year-old Holland Park electrician was picked up by Carstens on April 19. His bags were packed and he had with him valuable diving equipment.

His family knew he had found work as a salvage diver. But as the weeks went by and he didn’t write, they became concerned. It wasn’t like Bruce not to stay in contact. Theirs was a close family.

Kerry Rowan disappeared on April 25. The 19-year-old’s story was the same as Bruce’s. He’d left with expensive diving equipment to work on the Cutty Sak. And he never came back.

THE STORY hit the front page in December. By then, even Carstens was listed as a missing person.

“Four vanish on diving trip,” the headline read.

“The mystery 10-month-old disappearance of two men and two youths from Queensland, yesterday erupted into a major homicide investigation.

“They each left their homes believing they were headed for a scuba diving expedition off north Queensland or New Guinea.

“Police fear for their lives and believe they could be dead, possibly murdered. It was also possible they could have been shanghaied for ship’s crew.”

Journalists spoke to Bruce Peters’ mother, Thelma, who insisted she should have heard from her son by now.

“Bruce is a home-loving boy … our only son … and when he’s been away before he’s always kept in touch with us.”

Carstens had driven a white 1964 Mini Cooper with a red roof when he’d collected Kerry and Bruce from their homes. They released the description, as well as the registration plates, in the hope a member of the public might spot the vehicle around Brisbane.

It worked. Within days they had Carstens. He’d been spotted in Townsville driving the stolen Mini Cooper. He’d run into the bush when police had pulled him over and it had taken them another two days to find him.

When they did, they found him carrying a bottle of strychnine poison. He gave them no reasonable explanation for having it.

They hauled him into court and a Magistrate sent him to prison for eight months. It was a good result. With Carstens cooling his heels, detectives had time to find the others.

It would become the biggest manhunt the country had ever seen. Inquiries were made in New Guinea, Indonesia, Borneo and Canada. Interpol officers based in Paris assisted Queensland police.

They searched high and low, but they did not find the Cutty Sak.

Police became convinced the boat could not be found. It did not exist.

In July, 1971, they charged Carstens with three counts of murder.

HE’D TOLD them the Cutty Sak and its crew were in the north of the country. They were alive and well but he would not give them an exact location. The Cutty Sak, he explained, was up to no good. They’d been engaging in illegal activities – running drugs and pilfering wrecks. More than that he would not say.

He promised he could contact them by radio – but only if he was released from jail.

And he couldn’t let them come home. They might talk and he’d end up with a lengthy prison sentence.

Police knew better than to believe much of what came out of Carstens’ mouth.

A Magistrate listened to the evidence at that first hearing and remanded Carstens in custody until his next appearance on July 14.

He asked Carstens whether he agreed.

“As long as it is no longer than the 14th, Your Honour,” an arrogant Carstens replied.

CARSTENS SPENT his time in prison writing letters to the parents of his victims. If they helped him get out, he promised to return their children.

The police were playing their own games.

Bruce’s mother, Thelma Peters, carrying a small tape recorder when she and her husband went with Carstens’ father to see him in jail.

“I’ll give you a name,” he told them.

John Gabriel of CPC Pest Control in Darwin would help them, he said. He’d get them on a plane to where the boys were on a launch around the Celebes group of islands.

He wouldn’t give them the exact location though. There were others involved in the drug running operations and they could all land in jail.

“If it was only 12 months, I would not hesitate,” he said to Bruce’s grieving parents.

“But there is a lot more involved than that.”

Mrs Peters was furious.

“Why do you tell so many lies? Look! You know what I think? I honestly feel that you have done away with these boys – my boy anyway.

“Now all we want is to give him a decent burial. Why don’t you tell us where he is?”

He told her again that he knew where they were, that they were alive. That only he had control over their fate.

“I’m 25,” he said – and even that was a lie.

“I’ve had dealings with the police for the past 15 years. I don’t go with them telling me what to do.

“This time they are going to do what I say or they’ll fall into a hole.”

He looked at Thelma Peters.

“You will see your son again,” he said.

She asked him whether he believed in God.

“In a sense, yes,” Carstens said.

“Don’t you think he will make you pay for this?” she asked.

“In time, maybe,” he said. Then: “Yes.”

AROUND 100 witnesses were called to give evidence at Carstens’ trial.

One of them was Detective Inspector Bill Taylor – an old-school cop who would doggedly pursue Carstens until the end.

In June, he’d been to see the accused murderer in prison. A recording of their conversation as played to the jury.

“I can still contact the boat,” he’d told the detective.

An associate named Ronnie could get in touch with them.

If police released him from jail, he’d have the boys home to their families in four days.

On June 22, Carstens had put his demands in writing to the detective.

Following the failure of authorities to release him, he wrote, he’d had no choice but to order that the boys be put ashore on an island north of Australia.

They were in a very bad area with poor communications.

But there was still time to collect them, Carstens added. He was presenting police with his final offer.

Carstens was to be released from prison by July. He was to be met by only his wife and father and a third person – either the father of one of the missing boys or a newspaper journalist.

Those three people would go with him to collect the missing boys and only those three. No police.

And he wanted a written guarantee of immunity from arrest no matter what the boys might say on their return.

Police ignored him.

The jury listened as another witness took the stand. Allan Sganzerla gave evidence about a conversation he’d had with the accused man prior to his arrest.

He and Carstens had been talking about boats and diving when the conversation took a more sinister turn.

If your diving companion somehow died, Carstens began, how would you get rid of the body?

I’d report the death to the water police on the two-way radio, Sganzerla said.

“But just supposing you wanted to hide the body or supposing somebody was killed and you wanted to still get rid of the body, could you wrap it in wire netting and weigh it to the bottom,” Carstens pressed.

“That wouldn’t be any good,” Sganzerla said.

“Somebody’s anchor would get stuck in it for sure and would pull it to the top and that would look suspicious even if it was an accident.”

Carstens continued.

“Supposing you were diving and your mate got killed … or suppose you had your enemy and you wanted to kill him and get rid of him and completely dispose of his body, what would you do?”

The other man’s reply was enough to bring the sound of weeping from the public gallery.

“Well, if you had to throw it into the sea, the best thing you’d have to do is cut it into pieces. That way it would sink and wouldn’t float. That way the fish and sharks would eat it.”

The prosecution told the jury that extensive searches had failed to find any trace of the Cutty Sak. In fact, police believed it did not exist, had never existed.

Carstens had been caught in a “web of lies”, posting the advertisement to continue his ruse with 16-year-old Peter’s family. That, in turn, had led the others to their deaths.

He’d killed them because there was no boat. And because they were carrying expensive diving equipment. With the others missing, he could claim there really was an ocean expedition. He’d been slowly murdering himself a crew of divers and deckhands.

His stories over the months they’d been visiting him had become more and more elaborate. The Cutty Sak was being used to salvage old Army equipment off the coast of Queensland, he told them.

They’d recovered cases of old guns and sold them in North Vietnam. Many of his stories were contradictions of previous versions. Police believed none of it.

The court also heard from a man who had gone diving with Carstens. He told the jury Carstens had sold him a tank and a regulator. Later he’d sold him a wetsuit. The equipment had been handed to police, who showed it to the parents of the missing boys. Thelma Peters identified it as the same as items belonging to her son Bruce.

The trial lasted 17 days. After hearing all the evidence, the jury of 12 took just two hours and 35 minutes to reach their verdict: Guilty.

“There is only one sentence for a crime such as this,” Justice Lucas told Carstens.

“Perhaps you did not appreciate how base and scoundrelly your character has emerged during the course of this trial.

“I sentence you to imprisonment with hard labour for life.”

Carstens stood at ease, slowly chewing with his hands behind his back when he was asked whether he had anything to say.

“Nothing,” he replied, with exaggerated casualness.

BRUCE Peters’ killer had not even bothered to dig him a grave.

It was the middle of nowhere, after all. It could be years before anyone found the young Holland Park electrician.

It had been an execution-style killing. Alexander Carstens had stood behind his terrified victim, held out his gun and pulled the trigger. Once. Twice. Two shots to the back of the head.

The bull-like meatworker had not taken any chances. And he was right. It was two years before hikers stumbled across the remains of young Bruce.

He’s left Thelma Peters’ only son in an overgrown area of scrub, 175km northwest of Brisbane near Blackbutt.

It was a place where scrub turkeys roamed and dug out nests in the dirt.

Bruce had been covered in soil and branches and left in the open. He was still wearing the orange shirt he’d been killed in. His natural fibre trousers had mostly rotted away.

Police gathered an army of volunteers to search the bush for more bodies. But the search proved fruitless. They could not search such a vast area. Even if Carstens had driven a kilometre on to dump another body, they’d never find it in such dense scrub.

And then, more potential victims began to emerge.

Det Insp Taylor, who’d pursued Carstens so doggedly, told journalists he believed Carstens’ body count was at least seven.

One, 16-year-old Carol Ann Pinches, had been mentioned during the trial.

Carol had been a close friend of Peter Colburn’s and had disappeared from her family’s Riverview home a few days before the young meatworker went missing.

In prison, Carstens had told a detective he knew where she was buried. He later denied mentioning her.

“My mother’s life is a misery,” Carol’s brother told The Courier-Mail three years after she disappeared.

“She has nightmares, gets highly emotional and hysterical. It’s because my sister is missing. She is dead. She has been murdered.”

ALEXANDER Carstens was not content to sit in jail.

He lodged an appeal that went nowhere. In 1974, he was involved in a plot where a letter was written to the police commissioner threatening to blow up City Hall if a number of prisoners – he among them – were not released.

In 1980, he was moved out of maximum security into the medium-security Wacol Prison.

Retired Assistant Commissioner Normal Gulbransen was furious.

“I would not trust him anywhere, anytime,” he said.

“He is one of the last in the world I would recommend for medium security.

“The administration is sticking its neck out too far this time.”

Retired Brisbane Jail superintendent Roy Stephenson agreed.

“As far as I was concerned, I ordered Carstens kept under double maximum security,” he said.

Joan Colburn, whose son Peter was Carstens’ first known victim, was even more direct.

“I would use my shotgun on him,” she said. “And I would shoot to kill.”

“He will escape from there for sure. And when he does I will join the police search for him. That’s when I’d use my shotgun on him.

“I think he should have been hanged in the first place – but now he’s getting the soft life on a prison farm.

“It’s only a matter of time before he breaks out of there.”

IN 1987 he was moved again. This time to a low-security prison farm called Palen Creek.

For the mothers of the missing children – some who’d had threatening letters sent to them from Carstens in prison – it was more horror, more fear, more disbelief.

“He could just walk out if he wanted to,” Joan Colburn said.

And he did. The following year.

“Whoever’s responsible for moving him needs a swift kick in the backside,” retired jail superintendent Roy Stephenson said, calling Carstens a “psychopath”.

“Carstens would never have reformed.”

Mrs Colburn was offered a police detail at her home, for her safety. She was having none of it.

“I will be shooting to kill if he comes,” she said.

Thelma Peters wanted him dead too.

“Carstens is a psychopath, a compulsive liar and a conman. I just hope they shoot the bastard, save the taxpayers’ money and let us get on with our lives,” she said.

They found him four weeks later. Carstens had been hiding in dense mountain bushland in Northern New South Wales, living off wild fruit.

He’d been spotted by a passing car walking near a picnic area.

Police quietly sealed the area and borrowed a van from the local electricity council.

Dressed electricity workers, two officers quietly cruised the area until they spotted the fugitive.

They arrested him at gunpoint. He came without a struggle.

Three years later, he expressed confusion over authorities’ refusal to grant him parole.

“I believe I should be given the chance,” said the man who’d murdered three, probably more, without ever telling their families where to find the bodies.

He remains in prison today. Forty-five years after placing an advertisement in The Courier-Mail that would lure young scuba divers to their deaths, Alexander Carstens is behind bars at Wolston Correctional Centre.