Luke Huggard, age 31 was last seen by hospital staff at Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney when he was referred to an appointment at Camperdown. Luke did not arrive at this appointment. Luke has not been seen or been contactable since his release from hospital. Police hold grave concerns for Luke’s welfare.

If you have any information that may be able to assist Police, please contact Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000.

STATE CORONER’S COURT OF NEW SOUTH WALES Inquest:

Inquest into the disappearance of Luke Michael HUGGARD

Hearing Dates: 25 July, 26 July and 20 September 2023

Date of Findings: 22 March 2024

Place of Findings: Coroner’s Court of New South Wales at Lidcombe

Findings of: Magistrate Joan Baptie, Deputy State Coroner

Catchwords: CORONIAL LAW – unexplained disappearance and whether missing person is now deceased, date and place, cause and manner of death

File Number: 2018/00056509

Representation: Ms A Chytra, Coronial Advocate assisting the Coroner

Findings

The identity of the deceased Mr Luke Michael Huggard, who was reported as a missing person to New South Wales Police Force on 2 May 2017, is now deceased.

Date of death Mr Luke Michael Huggard died on 4 April 2017.

Place of death Mr Luke Michael Huggard died at Jacob’s Ladder, The Gap, Watsons Bay.

Cause of death: The available evidence does not allow for any finding to be made as to the cause of Mr Luke Michael Huggard’s death Manner of death Mr Luke Michael Huggard’s manner of death was self inflicted with the intention of ending his life.

Recommendations To the Executive Officer, Prince of Wales Hospital

a) If it is not already completed, the SSESLHD will continue with the planned rollout of training on the Mental Health Act, including components that specifically address the requirements under sections 71 and 72, the Nomination of Designated Carer Form and the escalation process for all clinical staff working in inpatient units.

b) That the SESLHD Document and Development and Control Committed (DDCC) will continue to consider the proposed changes to the admission, transfer of care and discharge checklists to include a specific prompt for the notification of a designated carer or guardian, and a prompt to record the reasons if a designated carer or guardian is not notified.

c) That the SESLHD will audit the Nomination of Designated Carer Forms at the Kiloh Centre for completion rates and accuracy

d) That the SESLHD will investigate options for a secure electronic document system that will allow the transmission of patient records from non-NSW Health entities as an alternative to the use of fax machines

e) That in the interim, the Kiloh Centre consider creating a specific role responsibility for following up requests for collateral information.

Introduction

1. This inquest concerns the disappearance of Mr Luke Michael Huggard.

2. Mr Huggard was born on 8 May 1985 in Victoria, Australia.

3. Mr Huggard resided independently at 18/35 O’Dea Avenue, Zetland.

4. At 5.49pm on 4 April 017, Mr Huggard was discharged from the Kiloh Centre at the Prince of Wales Hospital. He had been an involuntary patient at the Kiloh Centre since 1 April 2017. At 4pm on 2 May 2017, a social worker from the ACON organisation contacted police with her concerns for Mr Huggard’s welfare. The social worker informed police that Mr Huggard regularly attended a weekly appointment with her service, however, he had not attended any appointment since 30 March 2017. The New South Wales Police Force (NSWPF) commenced a number of enquiries as to the location and wellbeing of Mr Huggard. Unfortunately, all enquiries have been unable to establish the current whereabouts of Mr Huggard. After all existing lines of enquiry to locate Mr Huggard had been exhausted, the NSWPF submitted a report to the Coroner on 19 February 2018, indicating that it was suspected that Mr Huggard was deceased. Mr Huggard’s family have been present during these proceedings and have provided extensive assistance to the investigating police and the Coronial Advocate assisting. I acknowledge the unimaginable difficulties his family are experiencing with the lack of conclusive evidence relating to Mr Huggard’s whereabouts and fate. I would also like to acknowledge and thank his family members for their contribution and participation in this inquest. I hope that Mr Huggard’s memory has been honoured by the careful examination of the circumstances surrounding his disappearance and his treatment at the Kiloh Centre.

9. At 4pm on 2 May 2017, a social worker from the ACON organisation contacted police with her concerns for Mr Huggard’s welfare. The social worker informed police that Mr Huggard regularly attended a weekly appointment with her service, however, he had not attended any appointment since 30 March 2017. The New South Wales Police Force (NSWPF) commenced a number of enquiries as to the location and wellbeing of Mr Huggard. Unfortunately, all enquiries have been unable to establish the current whereabouts of Mr Huggard. After all existing lines of enquiry to locate Mr Huggard had been exhausted, the NSWPF submitted a report to the Coroner on 19 February 2018, indicating that it was suspected that Mr Huggard was deceased. Mr Huggard’s family have been present during these proceedings and have provided extensive assistance to the investigating police and the Coronial Advocate assisting. I acknowledge the unimaginable difficulties his family are experiencing with the lack of conclusive evidence relating to Mr Huggard’s whereabouts and fate. I would also like to acknowledge and thank his family members for their contribution and participation in this inquest. I hope that Mr Huggard’s memory has been honoured by the careful examination of the circumstances surrounding his disappearance and his treatment at the Kiloh Centre. In these findings I have referred to Mr Huggard at various times as Luke. This is not meant as any disrespect to Mr Huggard or his family. Rather, it is to acknowledge the nature of the person who has been described during these proceedings as a person who “stood for the marginalised. He wanted every single person that he met to feel heard, to feel welcomed and to feel loved. Luke absolutely loved people. He also had a wicked sense of humour. He had an energy that encompassed the room. You could never forget his infectious laugh.” The role of the coroner and the scope of the inquest.

11. When a case of a missing person who is suspected to have died is reported to the Coroner, the Coroner must determine from the available evidence whether that person has in fact died. If a Coroner forms the view that a missing person has died, then the Coroner has an obligation to make findings in order to answer statutory questions about the identity of the person who died, when and where they died, and the cause and manner of their death. If the Coroner is unable to answer any of these questions, then an inquest must be held.

14. In Luke’s case, the missing person investigation conducted by the NSWPF has been unable to locate him or any physical evidence as to his location since 4 April 2017. As such, it is not possible to answer all of the questions that a Coroner is required to answer, and an inquest has been convened. During these proceedings, evidence has been received in the form of statements and other documentation, which was tendered in court and admitted into evidence. In addition, oral evidence was received from the Officer in Charge of the investigation, Detective Sergeant Michael Egan, Luke’s treating psychiatrist, Dr Malik, as well as treating doctors from the Kiloh Centre, including Dr Thanaskanda, Dr Koh and Professor Mitchell. An expert conclave was convened with three experts providing their opinions on a number of facets of Luke’s presentation and treatment whilst at the Kiloh Centre. The General Manager of Corporate Services for South East Health, Ms Carey also gave evidence. All the material placed before the Court has been thoroughly reviewed and considered. Written submissions have been received from each of the legal representatives representing the various parties and have been of assistance.

A Brief Overview of Luke’s Earlier Life

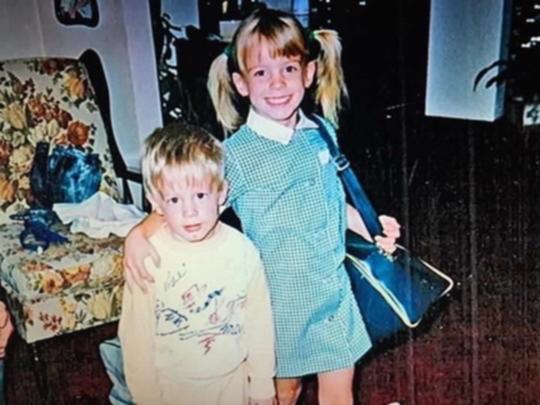

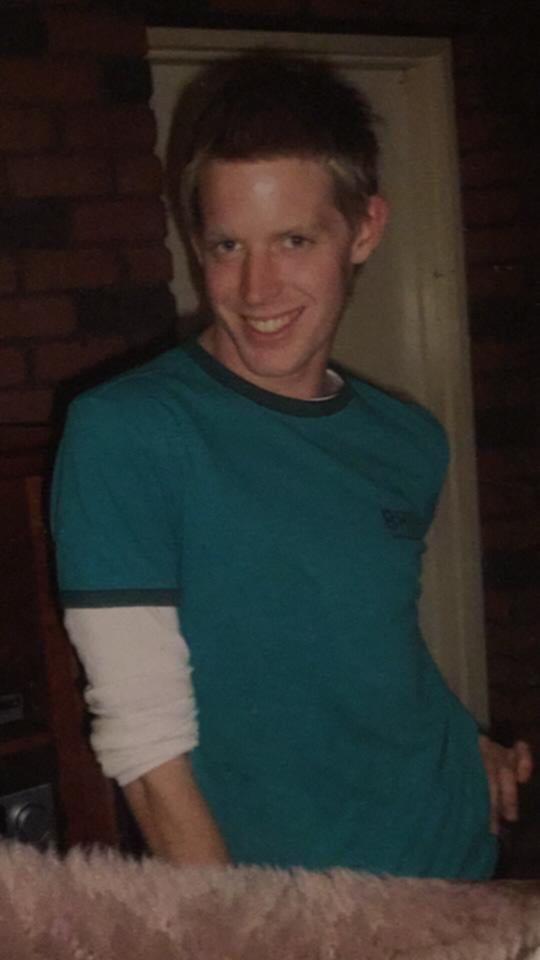

Luke was the second child of Mr Stephen Huggard and Ms Rosemary Cook. Luke has an older sister, Ms Jessica Huggard. Mr Stephen Huggard and Ms Rosemary Cook separated in around 2000. The children resided with Ms Cook for some time and then began residing with Mr Huggard about two years later. Mr Stephen Huggard indicated that it was around this time that he became aware that Luke was experimenting with cannabis. Luke completed his Higher School Certificate and enrolled to study a Bachelor of Arts at Melbourne University. During his time at University, he was actively involved in student activism and was a regular contributor to various magazines, including Q Magazine. He successfully completed his Arts Degree in political science and continued his studies in journalism. He later enrolled to study law in Sydney. In 2010, Luke attended at the Sydney Clinic for mood issues and drug use. He had a further admission to the Sydney Clinic in 2011. In 2012, he was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder by Dr Freed at the Sydney Clinic. In 2012 Luke’s father agreed to fund Luke’s attendance at a private residential rehabilitation clinic in the USA. He remained at the private clinic for approximately three months. During his admission he was diagnosed by Dr Botwin (USA) with schizoaffective and ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). He was prescribed lisdexamfetamine and mixed amphetamine salts. He continued to reside in the USA for two years before returning to Australia.

In 2015, he was admitted to the Melbourne Clinic following a suicide attempt. On 4 December 2015, he was admitted to the Hills Clinic and was treated by Dr Usman Malik over the following two years. His diagnosis of schizoaffective, ADHD, PTSD and Substance Use was considered to be in remission prior to, and after, the 2015 admission. His symptoms of schizoaffective disorder were noted to respond well to an antipsychotic medication known as lurasidone. His depressed mood was treated with antidepressants and his attendance at psychosocial groups. He was discharged on 17 December 2015. Luke had two further admissions to the Hills Clinic in 2016 and another admission in 2017. At times, Luke had a strained relationship with his father revolving around his sexuality, his drug use and his regular requests for money to supplement his Disability Support Pension payments. Despite this, he was regularly in contact with his family, as well as his friends. Luke was in regular contact with his social workers and counsellors from the Aids Council of NSW (ACON). He had also been referred to community mental health services, although it is unclear whether he engaged with these services.

Events leading up to his admission to the Kiloh Centre on 1 April 2017.

On 9 February 2017, Luke contacted Kings Cross Police Station who attended at his home. Police noted that Luke appeared to be under the influence of alcohol and drugs. His speech was erratic, and he complained that he was being investigated by police and unknown persons were creating gay dating profiles of him on the internet without his approval. He advised police that he was being treated by Mr Malik and had spoken to Dr Malik for about one hour that day. He stated that he had not taken his prescribed medications for the last two days and denied having any thoughts of self-harm or suicidal ideation. Police made a referral to the Camperdown Mental Health Team who confirmed that they would visit Luke that evening. On 24 February 2017, police again attended Luke’s home after receiving a call for assistance. Police perceived that Luke was paranoid and delusional. Luke told police that he was being investigated by police over false accusations from drug dealers in Surry Hills. He made no threats of self-harm and police contacted the Mental Health Line and were advised that his referral would be actioned by the Mental Health Team. On 7 March 2017, Luke was taken to St Vincent’s Hospital by ambulance as a voluntary mental health patient after a friend found him with multiple wounds to his forearms. He confirmed that he had cut himself with a Stanley knife. He told medical staff that he had experienced “mixed cycles – describes impulsivity, drug use. Now more flat depression and paranoia. State cut arms because he felt exhausted and wanted to kill himself. No longer wants to kill himself – wants to give it another chance.” Luke stated that he was using methylamphetamines intravenously and had last used two weeks earlier on a Wednesday. It was noted that he had previously been using 2 points (0.2 grams) daily. He was admitted overnight. On 8 March 2017, the hospital records note that his main support in the community is “my psychiatrist”, referring to Dr Usman Malik.

On 9 March 2017, Luke was admitted to the Hills Clinic as an inpatient. On 15 March 2017, Luke was granted leave from the Hills Clinic. He later attended a restaurant in Darlinghurst and was described as being intoxicated with alcohol. He left the restaurant without paying for his meal. Witnesses restrained him until police arrived and he was noted to have become aggressive towards the witnesses. Luke was later charged by police. He was dealt with by the Local Court in his absence on 4 April 2017 and fined $150. On 16 March 2017, Luke was discharged from the Hills Clinic for failing to abide by the facility’s leave policy. On 18 March 2017, Luke contacted triple zero and told the operator that he wanted to “confess his sins”. Police attended his home and noticed that Luke had healing lacerations to his wrists. Like was described as being in a manic state with his behaviour oscillating from laughing to yelling and stating that police and drug dealers were conducting surveillance on him. He told police that he wanted to kill himself and had planned to jump off the balcony of his apartment prior to the police attending his home. Police transported Luke to St Vincent’s Hospital seeking to have him scheduled to a mental health facility as an involuntary patient pursuant to section 22 of the Mental Health Act. At hospital, Luke denied that he has any current suicidal or homicidal ideation and denied that he had intended to jump off his balcony.

On 31 March 2017, Luke contacted the police who attended at his home. Police noted that Luke’s apartment was bare of all furnishings and was covered in rubbish. Luke told police that he had lost all of his possessions due to his mental health and drug use. He had arranged for his companion dog to be cared for by a friend. Police made a referral to the Mental Health Line. On 31 March 2017, Luke sent a number of text messages to his father, Stephen. At 8.16am, he wrote, “Hi Dad, can you please call me back, I’ve made some decisions”. At 8.40am, Luke sent another text to his father apologising for everything and wishing that he could get well and repay his father. At 1.57pm, he sent his father a text message telling his father that he had decided to go to hospital as he had relapsed once or twice over the past six months. A social worker from Redfern Health Centre contacted Luke by telephone at 5.04pm on 31 March 2017. Luke told the social worker that the situation had calmed down and that he had an existing support network and felt that that network could adequately support his needs. The social worker recorded that Luke sounded calm and settled and did not present as intoxicated during the conversation. Luke indicated that he would appreciate a follow-up call on Sunday 2 April 2017. 35. At 6.48pm, Luke commenced sending multiple erratic and abusive messages to his father. These messages continued into 1 April 2017. The stark contrast between his telephone call with his social worker at 5.04pm and the commencement of the abusive calls to his father commencing at 6.48pm on 31 March 2017, suggested that Luke had ingested either illicit substances or significant amounts of prescription medication.

Events on 1 April 2017

At 6.15am on Saturday 1 April 2017, Luke contacted triple zero from a public payphone at 505-509 Old South Head Road, Rose Bay. Luke was described as speaking erratically. He told the operator that a friend had taken his mobile phone and that a fraud was about to occur. At 6.17am, Luke again contacted triple zero and told the operator that “he feels like he is going to be violent to his father and murder him, his phone has been stolen, he doesn’t know where his father is and that someone has abused him.” Constable Clavel attended the vicinity of the public pay phone, however, was unable to locate any person. Constable Clavel then spoke with staff at the nearby Caltex service station. The service station staff confirmed that a male had attended and had requested some writing paper. They stated that he had then written two pages of notes stating that he was sorry and referred to killing his father. As police continued to search for Luke, he continued to send abusive text messages to his father. At 8.41am, Luke sent a text to his father stating, “Fuck you, dad and mum, I’m done, not saying anything and going to jump now. Bye.” Then, “Bye dad, I’m killing myself.” Followed by, “And I’m not doing it for them or you but for myself.” At around 9am, Constable Clavel was directed to the Lifeline phone at The Gap South on Old South Head Road near Derby Road in Watsons Bay. Luke had activated the emergency phone at Jacobs Ladder and a witness was waiting with him until police arrived. Constable Clavel spoke with Luke who stated that he was sick of life and wanted to kill himself. He described Luke as disordered in his thinking. Constable Clavel searched Luke and located the two pages of notes Luke had written earlier which stated that he wanted to kill his father.

Constable Clavel formed the opinion that Luke needed to be assessed and requested the assistance of an ambulance to transport Luke to hospital as an involuntary patient, pursuant to section 22 of the Mental Health Act. Paramedics attended the scene and observed Luke. The paramedics assessed Luke to be alert, oriented, agitated and emotionally distressed. Luke denied that he had suicidal or homicidal ideations to the paramedics, however they noted that he was unable to remain calm and appeared frustrated with domestic disputes. Luke was subsequently transported by ambulance to the Prince of Wales Hospital and detained in the mental health unit, known as the Kiloh Centre.

Admission and initial assessment at the Kiloh Centre on 1 April 2017

41. 42. 43. 44. Luke was admitted to the Emergency Department at the Prince of Wales Hospital at 10.27 am. A urinalysis was conducted which detected the presence of amphetamines. Luke was transferred to the Kiloh Centre, and a mental health assessment was conducted by Dr Anna Ferdman, Psychiatric Registrar. Dr Ferdman compiled extensive notes from her consultation with Luke which have been tendered in these proceedings. Dr Ferdman noted that he had a history of “schizoaffective disorder, substance misuse and multiple admissions to mental health facilities and drug rehab programmes. Luke presented agitated, distressed, shouting and emotionally labile. He required 20mg diazepam PO + olanzapine 10mg PO + droperidol 10mg IM to treat agitation.”

Dr Ferdman noted the following, “Luke explained a complex delusional system which centred around him being monitored by phone, wifi and through cameras in his air con vents. He also thought that messages received on his phone were also being controlled. He believed he was being monitored by the “law enforcement” who were investigating fraudulent allegations made against his father by his mother, and these included that Luke’s father is a paedophile (which Luke denies). He thought he had been under investigation for 15 years and related this to drug dealers in the surry hills area, as well as his mother. He believed that due to this investigation his father had not been in contact with him. He had spoken to his father recently and believes his father said to him “they (police) said you have to kull (sic) yourself or I’ll be charge with paedophilia”. Which is why Luke had gone to the gap with a plan of jumping. He denied symptoms of depression recently but spoke about the distress that this “investigation” was causing his father. He thought “undercovers (police)” were “everywhere” including the ED, and he was being watched and followed. He also thought that he could hear neighbours saying “rich father fraud.” Luke also reported injecting methamphetamines on Monday – unsure how much. He had also been taking excess lisdexamfetamine “to stay up” because of concerns about his father and being watched. Luke denied thought insertion or broadcasting. He did not believe others could control his actions. Denied low mood or guilty ruminations. Has attempted suicide a few weeks ago and says he has been feeling suicidal since then. Luke still thinks that he has to die in order for his father to be cleared of charges.”

Dr Ferdman recorded her contact and discussion with Mr Stephen Huggard, Luke’s father, as follows, “He was upset about the “privacy act” saying that he thought that privacy leads to death of people (sic). He thinks that he is “left in the dark”. Spoke at length about frustration of the privacy act and his inability to source any information, sees this to be the cause of doctors. Angry that we have called on a private number, etc. Says that this has been an issue since Luke was 14. Was initially reluctant to engage to due (sic) frustration about only being given limited information (previously).

Due to Luke being under MHA (Mental Health Act) and allowing me to speak with father I gave Steven a summary of this presentation.” The notes continue, “When Luke is unwell, he has variably said that he does not want family to know any information. Today Luke has called him 18 times from 8 different phone numbers. Father says that his use of drugs is “a disgrace”. Makes accusations of family. Rants and raves and speaks quickly at times. Often says that Americans are listening. Was in the USA for 3 months of treatment – private drug and alcohol rehab in Malibu, “then became a party boy.” At that point also expressing delusional content about phone being tapped – although father acknowledges that US govt does track certain conversations. Frequently deceptive and “hysterical”. Threatens self-harm when he wants finances from father, and this is declined. Usually very articulate. Has periods of being coherent but could not say how long. No other supports apart from Steven “he has burnt all bridges.” Steven feels that he has used up all his opportunities to get better. Luke has a history of self-discharging. Oppositional behaviour started when he left mother’s home.”

Treatment notes from the Kiloh Centre between 1 – 4 April 2017 45. 46. 47. 48.

The Kiloh Centre treatment notes record his use of lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) on 1 April 2017 at various entries in the hospital records. It appears that Luke had previously been prescribed an 80mg daily dose of lisdexamfetamine. Dr Ferdman noted that “He had also been taking excess lisdexamfetamine “to stay up” because of concerns about his father and being watched.” Dr Ferdman also noted that Luke had last used methylamphetamines intravenously last Monday (six days earlier). On 2 April 2017, a registered nurse recorded that Luke had stated that he had last used 1 bottle of dexamphetamines on 01/4/17. On 4 April 2017, Dr Jonathan Koh, Registrar, notes “Psychotic symptoms settled rapidly within 48 hours, and patient presented with narcissistic and antisocial traits at baseline, stating was confused due to taking 10 tablets of prescribed lisdexamfetamine on day of presentation.”

On 2 April 2017, the treatment notes recorded Luke as appearing “Superficially settled but some underlying irritability, guarded and can be dismissive.” His thought form and content is described as “Delusional processes, thought disordered, flight of ideas, at times seems preoccupied.” He is referred to as being “isolative” and paranoid and stating that he doesn’t “see why he has to be in hospital.” On 3 April 2017, Dr Koh records that Luke is preoccupied with needing to attend Court on 4 April 2017and “has to go home, get organised and pack up as is moving to Melbourne”. Dr Koh recorded Luke telling him that he was “dropped off at petrol station, states was “confused” as had ingested prescribed lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) from US psychiatrist (states was there until 2012) x 10. Denies use of other illicit substances.” Dr Koh records his impression of Luke as “Amphetamine-induced psychotic episode currently resolving with ongoing evidence of paranoia. Background of likely antisocial/narcissistic personality.” At 10.24am on 4 April 2017, Dr Shiamalan Thanaskanda reviewed Luke and recorded the following clinical notes, “Appeared quite sedated. Fell asleep on the bed while I was examining him, however straight after the examination stated that he was hungry and walked out in search of biscuits. No noticeable tremor, however, weakened power noticed in upper, lower limbs and facial muscles. Unsure if this is due to fatigue or neurological deficit. Coordination and balance also appears to be impaired but unsure if this is due to neurological deficit or if it was because he had olanzapine and diazepam quite recently. 50. 51. 52. 53.

54. Dr Thanaskanda then recorded under the heading “Plan” “r/v (review) in two days after he has stabilised.” At 3.38pm on 4 April 2017, a registered nurse recorded the following notes, “dishevelled, dressed in nightwear” and “spending most of his time in his room, appears sedated from medication but denies same.” His mood/affect is recorded as “flat and restricted” and his thought form/content is recorded as “Appears normal”. He is noted to be “oriented to time, place and person.” At 4.21 pm, Luke is reviewed by Professor Mitchell, Dr Koh and Dr Thanaskanda. Dr Thanaskanda was tasked with recording the progress notes, which stated “Impression: Drug induced psychotic episode with borderline, narcissistic traits. Improving mental state and good insight into the fact that he is mentally ill. No more current suicidal ideation”. Under the heading “Plan” it is recorded “Discharge today. Liaise with TCT (Transitional Care Team) team to visit him on discharge. Continue attending the stimulant team in Darlinghurst. GP to liaise with community mental health team.”

Dr Thanaskanda also records the following, “I don’t have family or friends here, so I need a support group or a case manager. I have a GP. I have limited contact with my Dad on the phone. I haven’t had a lot of face to face contact with relatives since I was 16 years old.”

Luke was discharged from the Kiloh Centre shortly after his review at 5.49pm.

Events at Jacobs Ladder, The Gap from 8.38pm on 4 April 2017

55. 56. At 8.38pm on 4 April 2017, the motion-activated camera located at Jacob’s Ladder, The Gap at Watson’s Bay was activated. The motion activated cameras have been installed by Woollahra Council and are monitored by a security company, Yates Security. As soon as motion is detected at the site, a video file is recorded and forwarded to Yates Security. The security officer employed by Yates Security was able to detect a person on the wrong side of the fence, closest to the cliff edge. He alerted police and officers attached to the Rose Bay police command commenced driving to the location. At 8.41pm, the security officer advised police that the person detected on the camera had jumped from the cliff ledge into the water. Police arrived on scene at 8.45pm and commenced searching the areas north and south of the site. An ambulance rescue helicopter was deployed to the scene and assisted searching the ocean and the cliff base. At the time there was a significant ocean swell which prevented NSW Water Police from commencing their search due to the hazardous conditions. The search was discontinued for the evening.

57. 58. 59. 60. 61. 62. On the morning of 5 April 2017, the search resumed with the assistance of the Police helicopter, Police Rescue and Water Police. The co-ordinated search continued on 6 April 2017, without success.

On 5 April 2017, Detective Reynolds was tasked with investigating the person’s disappearance and identification. Detective Reynolds conducted a search of the area in an attempt to locate personal items and CCTV. The footage from the motion-activated cameras was reviewed, however, due to the activity occurring at night, the footage records infra-red images only. Detective Michael Egan, the OIC of Luke’s case, also reviewed the footage. He stated that the footage shows a person sitting “on the edge and peers over it, moving positions several times. The person then climbs slightly down the rock face and makes their way across the wall. The person returns to the top of the bluff and walks north. The footage being in infra-red shows just the outline of the person. I form the opinion that the person is a male of a height at least of 180 cm. The person is of a thin build, has pants on and a hooded jumper which is over his head.”

Over the following weeks, Detective Reynolds made a number of enquiries with the State Transit Authority (STA) to determine if any buses had transported a person of a similar description to the nearby area, without success. Detective Reynolds also made enquiries with the Combined Communications Office, which records all recorded taxi fares in the metropolitan area. He received information in relation to nine relevant taxi fares, however, none were consistent with a taxi ride from the Prince of Wales Hospital to Watsons Bay. Similarly, his enquiries with Uber produced no useful information. Detective Reynolds obtained a spreadsheet from the Missing Persons’ Unit relating to persons reported missing between 27 March to 4 April 2017.

Detective Reynolds was also provided with a list of 29 persons who had been scheduled pursuant to the Mental Health Act by Rose Bay Police in the preceding weeks. Luke’s name appeared on that list; however, he had not been reported as missing at that time.

At 4pm on 2 May 2017, Ms Barr, a social worker at ACON contacted police with her concerns for his welfare. Ms Barr indicated that Luke would regularly attend his weekly appointments with her service, however, had failed to make contact since 30 March 2017. Ms Barr further noted that she had been advised by a number of Luke’s friends that they had attended his home on various occasions and had not been able to make contact. They also confirmed that there were no items of furniture of other belongings at his home and that he had given away or sold all his possessions recently, including his pet dog. Ms Barr confirmed that his friends had not been able to contact him through social media or on his mobile phone.

Police commenced making enquiries into Luke’s whereabouts and listed him as a missing person. Police confirmed that his bank account had no recent activity except for the Centrelink payments made on 10 April and 24 April 2017 and a debit for pet insurance. Enquiries were made with City West Housing, hospitals, air travel and mental health facilities, with nil result.

64. 65. In July 2017, Detective Egan was allocated the investigation into Luke’s disappearance. Detective Egan made contact with Luke’s mother and sister and a friend, Kylie, on numerous occasions. They confirmed that they had had no contact with Luke since March 2017. Detective Egan gave evidence in these proceedings and confirmed that he had recently conducted further “signs of life” enquiries and stated that “there hasn’t been any interaction, um, there hasn’t been any contact with any government authority, police, medical or otherwise, unfortunately,” since 4 April 2017.

Was Luke’s treatment at the Kiloh Centre from 1 April until 4 April 2017 appropriate?

66. 67. During Luke’s involuntary admission from 1 April to 4 April 2017, he was treated by Dr Ferdman, Psychiatric Registrar, Professor Philip Mitchell, Consultant Psychiatrist, Dr Pui Hon Koh, Psychiatric Registrar and Dr Shiamalan Thanaskanda, Junior Medical Officer/intern. During this inquest a number of issues have arisen relating to Luke’s care and treatment whilst an involuntary patient at the Kiloh Centre. These issues have included:

a. What was his correct diagnosis where there was a realistic differential diagnosis available on the objective and subjective presentation of the patient,

b. whether Luke’s reported intravenous use of methylamphetamines six days earlier or his excessive ingestion of his prescribed lisdexamphetamine on 1 April 2017 was the basis for his diagnosed drug-induced psychosis

c. whether the collateral information sought from the Hills Clinic and Redfern Health Centre would have assisted or altered the diagnosis

d. whether a family member or next of kin was nominated in accordance with the Mental Health Act 2007.

e. the accurate recording of treatment notes

The evidence of Dr Thanaskanda

68. Dr Thanaskanda provided a statement in these proceedings dated 31 May 2021. Dr Thanaskanda confirmed that he had prepared the clinical note dated 4 April 2017 at 10.24am. In his statement, he referred to the documented “plan”, being that Luke was to be reviewed in two days time. He provided clarification to the effect that “I documented that the plan was to review Mr Huggard’s condition in 2 days (assuming he remained admitted). In usual practice, it would be assumed that the drowsiness would have resolved by the time of the next review. In the event Mr Huggard continued to appear drowsy or had deteriorated further in the interim, further investigations would be undertaken. It is not uncommon for patients to be discharged prior to the next review taking place if the drowsiness has resolved.”

69. 70. 71. 72. 73. 74. 75. 76. Dr Thanaskanda confirmed that he had prepared the clinical notes documenting the ward round review with Professor Mitchell and Dr Koh at 4.20pm on 4 April 2017. He confirmed that he had no independent recollection of the review with Mr Huggard at that time. Dr Thanaskanda confirmed that he did not document that Luke was drowsy or sedated and opined that the lack of reference to sedation suggested that Luke’s drowsiness had resolved. Dr Thanaskanda confirmed that the treating teams’ impression at the review was that Luke had “experienced a drug induced psychotic episode with borderline and narcissistic personality traits but that his condition had improved at the time of our review. I documented that Mr Huggard demonstrated good insight into the fact he had mental illness and that he was not experiencing suicidal ideation.” In his statement, Dr Thanaskanda stated that he believed that he had not been asked to contact Mr Huggard’s next of kin and that he would document any attempts he had made, including any unsuccessful attempts at contact. Dr Thanaskanda also confirmed that he had no recollection of Mr Huggard refusing to provide consent to the treating team contacting his next of kin at that time. He noted that “there is no next of kin documented on page 11 of his medical records, so it remains possible that Luke did not nominate a next of kin to be contacted.”

Dr Thanaskanda confirmed that he played no role in contacting Dr Malik or the Hills Clinic for clinical notes. Dr Thanaskanda gave oral evidence in these proceedings on 25 July 2023. He confirmed the contents of his statement. Dr Thanaskanda confirmed that “as the intern, it’s not in the normal practice to initiate that discussion (about the next of kin) unless it was directed by, um, my superior, either the registrar or the consultant to initiate that discussion. But, um, normally it’s not for the intern to initiate that discussion.” Dr Thanaskanda agreed that it was a possibility that the subject of consent had been discussed during the review and that he had failed to record the discussion in his notes.

The evidence of Professor Mitchell

77. Professor Philip Mitchell is a professor of psychiatry at the University of NSW and also works at the Ramsay Clinic Northside Hospital in Sydney. Professor Mitchell was a clinical academic and consultant psychiatrist at the Kiloh Centre in 2017 at the time of Luke’s admission.Professor Mitchell indicated that he did not have access to the electronic medical records as he was a visiting consultant/clinical academic. He noted in evidence that there was no “paper” file available for Luke. Professor Mitchell prepared a statement dated 11 October 2021. He stated that “my practice in ward rounds has always been to first have the registrar (in this case, Dr Koh) present the case in detail, after which I would ask the responsible nursing staff (in this case RN Charles) for his/her observations of the patient. After that, I would always interview the patient face-to-face in the presence of the other staff members…Details of the ward round discussion were entered by the JMO (Dr Thanaskanda).” Professor Mitchell confirmed in his statement that on 4 April 2017, Luke was “no longer psychotic or suicidal, which was consistent with his having experienced a psychotic episode due to amphetamines (where the psychosis settles within a few days of cessation of the amphetamines). As noted in the ward round notes, it was likely that there were also significant personality traits.” In oral evidence, Professor Mitchell confirmed that his diagnosis of Luke at the time of the ward round on the afternoon of 4 April 2017 was that his druginduced psychosis had resolved. Professor Mitchell acknowledged that Dr Malik had been Luke’s treating psychiatrist for a significant period of time, however, Professor Mitchell indicated in evidence that he felt confident in his diagnosis that Luke’s psychosis had resolved and would have contacted Dr Malik if he had believed such contact would have been critical to his decision-making on 4 April 2017.

Professor Mitchell stated that it would usually be the role of a junior doctor to contact the treating doctor, such as Dr Malik, to verbally obtain the additional information, although at times the consultant would contact the treating psychiatrist if deemed necessary. Professor Mitchell confirmed that he had been made aware during the ward round that Luke had indicated that he no longer wanted to consult with Dr Malik. Professor Mitchell indicated that Luke’s indication would not have affected Professor Mitchell’s decision whether to contact Dr Malik or not if he believed that information would have been of assistance. Professor Mitchell confirmed that he became aware that a request had been forwarded to the Hills Clinic for Luke’s treatment records on 3 April 2017 by Dr Koh. Professor Mitchell indicated that he became aware later that contact was made with the Hills Clinic and that the clinic had attempted to fax the records to the Kiloh Centre. Professor Mitchell stated that “It wouldn’t have made any difference to the decision if we’d had it (the records). You sometimes make decisions on the information you have, and I was comfortable the information I had was sufficient to make the decision on that occasion.” Professor Mitchell was referred to section 72B of the Mental Health Act, specifically in relation to Dr Koh requesting the records from the Hills Clinic. Section 72B states, “An authorised medical officer or other medical practitioner or accredited person who examines an involuntary patient or person detained in a mental health facility for the purposes of determining whether the person is a mentally ill person or a mentally disordered person or whether to discharge the patient or person is to consider any information provided by the following persons, if it is reasonably practicable to do so – a) any designated carer, principal care provider, relative or friend of the patient or person in relation to a relevant matter, b) any medical practitioner or other health professional who has treated the patient or person in relation to a relevant matter, c) any person who brought the patient or person to the mental health facility.

86. 87. 88. 89. Professor Mitchell initially responded “Well, they had, but the patient said he wasn’t returning to see Dr Malik. So, I don’t accept that that’s an ongoing responsible service.” Professor Mitchell was questioned as to whether it was reasonably practicable that that information was sourced by the treating team on 4 April 2017. He further commented “I didn’t think that it would have been relevant to the decision that was being made at that time.” He later commented “The intent had been there to do it. It wouldn’t have made any difference to the decision if we’d had it. You sometimes make decisions on the information you have, and I was comfortable the information I had was sufficient to make the decision on that occasion.”

Professor Mitchell confirmed that he was aware that Luke had previously been diagnosed with a schizoaffective disorder. He stated that he felt Luke’s presentation was consistent with an amphetamine induced psychosis. He agreed that there was information that Luke had told Dr Ferdman that he had last used methylamphetamines intravenously six days earlier, however he felt that someone as unwell as Luke may not have been accurate in regard to his recent drug taking history. He also accepted that it was possible for lisdexamfetamine to produce a type of drug induced psychosis, “Potentially if you took very large amounts of it. In practice, no. With normal therapeutic doses, no.” He continued to state “With approved therapeutic doses of Vyvanse of lisdexamfetamine. It’s highly unlikely that patients would become psychotic, highly unlikely. You do see it sometimes, but highly unlikely.” He confirmed in his opinion that Luke’s drug induced psychosis was more likely caused by the use of methamphetamines. Professor Mitchell was asked if Luke’s presentation was more consistent with an underlying major mental illness, such as his earlier diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder. Professor Mitchell commented “Look, possibly, but it was striking that the paranoid beliefs resolve very quickly which is not what you would expect if there was – if that presentation was due to a schizoaffective disorder.” He further noted that he would generally expect a drug-induced psychosis to resolve typically over a few days.

90. 91. 92. 93. 94. 95. 96. Professor Mitchell confirmed that Luke had been administered olanzapine and diazepam from 1 April 2017. He agreed that it would be standard procedure to administer the same medications to a person suspected to be suffering from a psychosis arising from a major mental illness. Professor Mitchell commented that in that situation, however, the pharmacological treatment would take several weeks rather than days to see a resolution of the symptoms. Professor Mitchell was referred to a number of occasions during February and March 2017, where Luke presented to the Redfern Health Centre, the Hills Clinic, NSW Police, NSW Ambulance and St Vincent’s Hospital with delusional thinking and/or psychosis. Professor Mitchell noted that on each occasion, it was unknown whether Luke had been using methamphetamines prior to his presentation or admission. Professor Mitchell was asked to comment on the proposition that more times a patient presented with drug-induced psychosis, the higher the risk that the person would develop a major mental illness. Professor Mitchell responded “I don’t think there’s evidence for that.” Professor Mitchell agreed that each time Luke was presenting with suicidal ideation it appeared to be whilst he was experiencing a psychotic episode. He noted, however, “There may be incidents where he was suicidal and not psychotic. So, you know, the difficulty is it’s very specific information I’ve been provided with.”

Professor Mitchell was asked whether his psychotic presentation on 1 April 2017 was a manifestation of his schizoaffective disorder. He stated “Yes. Part of my normal process is to exclude other reasons for the presentation, as well as the reason that I decided on. So we call that a differential diagnosis and so I would have excluded other reasons for the psychotic presentation. And I think we were aware. Psychiatrists differ. There are different opinions about diagnosis, and I always take into account colleagues’ diagnosis but end up making my own diagnosis on the information I have in front of me.” Professor Mitchell was asked whether the possibility that Luke committed suicide late on 4 April 2017 after his discharge from the Kiloh Centre made him question his diagnosis that his psychosis had resolved. He stated “No, it doesn’t. It was a tragedy and I just emphasise that if it was Luke that jumped off, but it doesn’t make me question the diagnosis.” He further stated that “At the time I saw him, he wasn’t a serious risk. Clearly, it was a tragedy what happened, and I think we’re all concerned about that.” Professor Mitchell was referred to section 71 of the Mental Health Act 2007. Section 71 states:

(1) The “designated carer” of a person (the “patient”) for the purposes of this Act is -

(a) ….. (b) ….. (c) if the patient is over the age of 14 years and is not a person under guardianship, a person nominated by the patient as a designated carer under this Part under a nomination that is in force, or

(d) if the patient is not a patient referred to in paragraph (a) or (b) or there is no nomination in force as referred to in paragraph (c) - (i) the spouse of the patient, if any, if the relationship between the patient and the spouse is close and continuing, or (ii) any individual who is primarily responsible for providing support or care to the patient (other than wholly or substantially on a commercial basis), or (iii) a close friend or relative of the patient. Subsection 2 provides a definition of “close friend or relative” and “relative” 97. 98. 99. Professor Mitchell confirmed that he was aware that Dr Ferdman had spoken with Luke’s father on 1 April 2017. In his statement, Professor Mitchell stated “I am not aware that Luke did not consent to a family member of friend not being contacted.” In oral evidence he stated “Yes. I became aware of that when I read the report from the local health history. I wasn’t privy to that at the time when he was under my care.”

Professor Mitchell commented that “patients don’t have to name a designated carer, but they are certainly encouraged to name a designated carer.” He further stated “The issue of the designated carer or next of kin is – that’s an issue that the nursing staff or administrative staff would look after. As the consultant, I am not involved in that side of it.” He agreed however, that he was involved in the final diagnosis and discharge planning of Luke. Professor Mitchell was then taken to section 79 of the Mental Health Act 2007.

Section 79 - Discharge and other planning

(1) An authorised medical officer of a mental health facility must take all reasonably practicable steps to ensure that a patient or person detained in the facility, and any designated carer and the principal care provider (if the principal care provider is not a designated carer) or the patient or person, are consulted in relation to planning the patient’s or person’s discharge and any subsequent treatment or other action considered in relation to the patient or person.

(2) In planning the discharge of any such patient or person, and any subsequent treatment or other action considered in relation to the patient or person, the authorised medical officer must take all reasonably practicable steps to consult with agencies involved in providing relevant services to the patient or person, any designated carer and the principal care provider (if the principal care provider is not a designated carer) of the patient or person and any dependent children or other dependents of the patient or person,

(3) An authorised medical officer of a mental health facility must take all reasonably practicable steps to provide any such patient or person who is discharged from the facility, and any designated carer and the principal care provider (if the principal care provider is not a designated carer) of the patient or person, with appropriate information as to the follow-up care. 100. Professor Mitchell confirmed “I am not aware of that specific issue in the Act. These are often decisions done by the team. So the issue of whether they had nominated a designated carer or next of kin, usually I would not be privy to it.” He continued, “The usual practice is that the hospital – and in practice I would emphasise that’s normally done by nursing or clerical staff – would inform the designated carer of the planned discharge.” He further noted when it was suggested that he would be the “authorised medical officer” pursuant to the legislation, “I think the – I mean, the authorised medical officer is the superintendent who delegates the responsibility to the consultant. So the consultant would not usually contact the family after a decision. It was usually a nursing or clerical. That was the way it operated in practice.” He was asked who is responsible for ensuring that it occurred, and Professor Mitchell responded, “I am not sure whether that would be the medical superintendent or the consultant.”

Professor Mitchell was asked hypothetically if Luke had declined to consent to allow his father to be notified of his proposed discharge from hospital on 4 April 2017, whether that had raised any concerns, particularly in light of Dr Ferdman’s notes prepared on 1 April 2017, where Luke’s father had indicated that “When Luke is unwell, he has variably said that he does not want family to know any information.” Professor Mitchell was of the view that there may be many reasons why a patient does not consent to the hospital notifying a designated carer, “not all of them psychosis. So I don’t think it necessarily means the patient was psychotic at the time”. 102. Similarly, Professor Mitchell did not believe that Luke’s decision that he no longer wanted to consult Dr Malik was due to psychosis and may have been attributable to a number of other considerations. The evidence of Dr Pui Hon KOH 103. Dr Pui Hon Koh is a staff specialist psychiatrist at the Kiloh Centre. At the time of Luke’s admission on 1 April 2017, he was a psychiatry registrar. 104. Dr Koh provided two statements in these proceedings, dated 21 July 2017 and 29 June 2021.

In his statement dated 29 June 2021, Dr Koh noted that “Dr Mitchell, Dr Thanaskanda and I agreed that Mr Huggard no longer satisfied the criteria for an involuntary admission, and that he was suitable for discharge. During the ward round, we sought consent to contact a family member of (sic) friend prior to discharge. In response to this request, Mr Huggard declined to provide consent to his verbatim response was documented as follows: “I don’t have family or friends here… I have limited contact with my dad on the phone. I haven’t had a lot of face to face contact with relatives since I was 16 years old.”

106. Dr Koh continued “In summary, Mr Huggard was suitable for discharge because there was no evidence of suicidal ideation, self-harm or harm to others, and he demonstrated signs of recovery such as insight, no confusion, future planning and a willingness to engage with future community treatment.”

107. Dr Koh further noted in his statement, “It is standard protocol for a patient’s nominated next of kin or support person to be notified about a patient’s significant treatment details and discharge under the Mental Health Act 2007 (NSW). As noted above, such a proposition was declined by Mr Huggard both during treatment and at the point of discharge. At the time of the ward round review on 4 April 2017, Mr Huggard demonstrated that he had capacity, and it was determined that he no longer satisfied the criteria for involuntary admission under the Mental Health Act. Based on the entry on 4 April 2017, the treating team had asked Mr Huggard for his consent to notify his father about the fact that he was to be discharged. As Mr Huggard was about to be discharged, his consent would have been required to make such contact.”

108. Dr Koh gave oral evidence in these proceedings on 25 July 2023.

Dr Koh indicated that he had no independent recollection of the circumstances surrounding Luke’s consent to contact family members. He stated “I think from the clinical notes, and you know, I don’t have an independent memory of us asking the question, but I can safely say based on kind of my clinical experience that it would be highly unusual for us not to have considered that in our mind or made some sort of inquiry about that”. He agreed that it was possible that “an inquiry was not made directly of Mr Huggard about whether he consented or not to someone being contacted.”

110. Dr Koh continued, stating “I think, um, along the lines of nominating next of kin or a designed (sic) carer, as the forms call it, it should be an issue that often is revisited over the course of the admission, um, as, you know, when patients get admitted, oftentimes that is the exact time point where it’s difficult for them to nominate someone. And so the expectation would be that as the clinical state changes, that would be revisited by usually the nursing – someone from the nursing staff. Um.”

Dr Koh was asked whether the clinical notes indicated that Luke had clearly expressed his direction that he did not want the hospital to contact a family member. Dr Koh responded, “Look, I don’t think it was a direct – I mean, it’s unclear whether that his response to a certain question but I – on review of the notes, I did think that there was evidence to think that, you know, he did express something along the lines that there was no-one that, you know, we could contact at that point.” Dr Koh’s statement and oral evidence at this point suggests that as Luke was to be discharged and was no longer an involuntary patient, the Mental Health Act no longer applied and the issue of notifying the designated carer was wholly dependent on the consent of the patient, even though the patient was not formally discharged as an involuntary patient.

112. Dr Koh later responded in his oral evidence, “I’m saying that based on the replies that were documented, um, it is not unreasonable to think that there would be some sort of, you know, refusal of us contacting them. Although that’s not documented entirely.” He then agreed that there was no refusal documented in the clinical notes. He further acknowledged that “I can’t say that he actually didn’t consent.” He was asked why he perceived that Luke was not consenting to contact and responded “Because it seemed like a very likely reply to a question that we would, you know, almost always, always, ask and consider at the point of discharge,” and then “As I said, I think that’s likely a response to some line of inquiry that we were wanting to find out what supports he had so that we could contact the right person.”

113. Dr Koh indicated in his oral evidence that he was familiar with the Mental Health Act and had a strong working knowledge of the Act.

114. Dr Koh indicated that he was aware that Dr Ferdman had spoken with Luke’s father on 1 April 2017. Dr Koh could not recall, in light of the contents of Dr Ferdman’s notes, why he had not asked Luke why he did not want the team to contact his father on 4 April 2017. He stated, “I can’t say it because I – I don’t know, I can’t remember what was asked or what wasn’t asked, but certainly it’s not documented.”

115. Dr Koh also noted, “Well, I think there are a few indications, um, for the earlier part of the admission, the first two days, he wasn’t engaging enough to, ah, discuss that topic and also, you know, no one had been filled out on the next of kin form. So that’s why the discussion wasn’t had.”

Dr Koh was asked about his understanding of section 71 of the Mental Health Act 2007, specifically relating to the designated carer. His response was “Um, I have to say it’s usual practice that when there’s – they’re not designated we don’t contact anyone unless there is circumstances that dictate that we have an urgent need to get collateral information.”

117. Dr Koh was asked “You were aware that Luke had a father. You were aware that Dr Ferdman spoke with his father. Luke didn’t nominate anybody to be his designated carer. Would you agree that pursuant to the legislation, in those circumstances, his father would have become the designated carer?” and Dr Koh answered, “Yeah. I would agree.”

118. Dr Koh was asked about his understanding of section 79 of the Mental Health Act 2007, and the need to notify the designated carer of the patient’s pending discharge. He stated, “Well, in my experience, when people are no longer under the Mental Health Act then they do not give an indication that they wish someone to be contacted. That doesn’t happen. I acknowledge what you’re saying. I think, yeah.” DR Koh indicated that “Well, I believe all my conversations with Luke are in the clinical notes” and further “All my conversations with Luke are in the clinical notes. I’m not aware that I had other conversations with him.”

120. Dr Koh was then taken to Luke’s delusional content relating to his father on 1 April 2017. He stated, “But definitely I would have explored his thought content in terms of what he had presented with. And if that was about the delusional ideas about his father, which I was aware of, which was a prominent part of the presentation into hospital, that would have been. Yes.” He then agreed that none of that is contained in the clinical notes. He stated that “Um, it’s difficult for me to recall because as I said I tried to do an assessment on hm but he was very uncooperative at that stage. I can’t recall whether I had put to him specific questions (on the 3rd of April).” Dr Koh was then asked, “Is it possible that you did not press him about his delusional thinking with respect to his father on 4 April?” and he responded, “Um, again, I think it’s not impossible but that’s not very likely.” He agreed that this was a significant issue due to the centrality of his father to his delusional thinking on 1 April 2017, with which he agreed.

121. Dr Koh confirmed that he had sought collateral information from the Hills Clinic on 3 April 2017. He indicated that he was aware that Dr Malik had previously diagnosed Luke with a major mental illness being schizoaffective disorder. He further confirmed that he was aware that Luke had had multiple admissions in the proceeding two months with similar symptomology. 122. Dr Koh confirmed that he had treated Luke with diazepam and olanzapine. He further confirmed that he would have administered the same pharmaceuticals if Luke had presented with schizoaffective symptoms with no suggestion of substance abuse.

Dr Koh agreed that his usual practice would have been to follow up with any request for collateral information. He indicated that he possibly did not follow up on this occasion due to workload. He confirmed that he understood that section 72B of the Mental Health Act required him to consider treatment notes from Dr Malik as Luke’s treating psychiatrist if it was reasonably practicable for him to do so.

124. Dr Koh confirmed that he had received and considered some collateral information, however, he could not be sure of the source of that information. He stated that the collateral information would be provided via a facsimile machine and would “usually be put in the paper file” and not on the EMR (electronic medical record).

125. Dr Koh confirmed that his impression of Luke’s condition on 3 April 2017, was an amphetamine induced psychotic episode, given that Luke’s urine drug screen had tested positive to amphetamines and that he was presenting in a psychotic delusional state. He agreed that it was unlikely that amphetamines would still be present in his system if he had last used amphetamines some six days earlier.

Dr Koh agreed that with any drug-induced psychosis, there was a risk that the patient would potentially develop a major mental illness. Dr Koh agreed that Luke’s delusional thought content was the product of either a drug-induced psychosis or a major mental illness. He indicated that “after every episode he would be at a higher risk of developing ongoing symptoms that would be more difficult to treat and eventually look more like a primary psychotic illness in terms of its clinical course.” He indicated that this process would likely take much longer than four weeks, and the time frame would be more likely years than weeks.

127. Dr Koh confirmed that lisdexamfetamine would register on a drug toxicology screen as amphetamine. He stated, “In my clinical experience, I’ve seen patients that are on lisdexamfetamine who present with pretty similar episodes.”

128. Dr Koh indicated that a diagnosis of a major mental illness on 4 April 2017 would not have changed his view that it was appropriate to discharge Luke “based on our assessment of his mental state that afternoon.”

The evidence of Dr Usman Malik

129. Dr Usman Malik is a medical practitioner holding specialist registration as a psychiatrist. He is a Senior Visiting Medical Officer at the St George Hospital and a foundation member of the Faculty of Forensic Psychiatry with the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.

130. In these proceedings, Dr Malik prepared two letters dated 3 October 2019 and 8 March 2021 and a statement dated 17 April 2023. Dr Malik confirmed that he had been Luke’s treating psychiatrist since 2015. Dr Malik gave oral evidence in these proceedings on 26 July 2023.

132. Dr Malik confirmed that he last saw Luke when he was admitted to the Hills Clinic in March 2017. He stated that Luke’s presentation on that admission was not in keeping with his previous admissions as he appeared to be “more distressed, disorganised and I think had to be discharged early due to disciplinary reasons which had never happened before.” On that occasion, Dr Malik felt that Luke was “suspicious and guarded and that even his behaviour at the restaurant just leaving without paying might be considered that he suddenly got scared or he felt persecuted and had to leave suddenly rather than intentionally leaving without paying.” Dr Malik commented that “I would say that the last admission was the most acute and previous admissions were not acute.”

133. Dr Malik also confirmed that Luke had no history of misusing his prescribed medications. 134. Dr Malik further confirmed that Luke had never refused to have his family or a support person contacted whilst receiving treatment at the clinic. The only family member Dr Malik recalled contacting on occasions was Luke’s father.

Dr Malik indicated that he only became aware that a request had been received from the Kiloh Centre for collateral information after the coronial investigation commenced. He stated that if he had been contacted by his treating doctors at the Kiloh Centre he would have “discussed the fact that he’s never been antisocial before. Like, he has always been polite. He’s always been on time. He’s never missed an appointment. He’s never shown any signs of anti-social behaviour as a private outpatient and therefore I’m concerned that this new behaviour, if you can call it that, is a sign of mental illness.”

136. Dr Malik confirmed that Luke’s previous diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder was current as at March 2017. He believed that the six separate episodes which occurred in February and March 2017, “could be drug-induced psychosis each time or it could be a schizoaffective or bipolar disorder each time or both. It could be both in some of those cases, like, both existing at the same time.”

137. Dr Malik was of the opinion that “depending on the number of episodes, the period of wellness in between episodes and the length of each episode” may present as a risk that his drug-induced episodes of psychosis could develop into a major mental illness.

138. Dr Malik was of the opinion that Luke was psychotic at the time of his presentation to the Kiloh Centre on 1 April 2017. Noting that Luke’s symptoms appeared to have resolved by 4 April 2017, Dr Malik was of the opinion that his diagnosis ‘leaned towards” a drug-induced psychosis, “but it doesn’t rule out other possibilities such as schizoaffective disorder.” He commented, “Because of all the episodes that you mentioned prior could have been part of that same ongoing longer episode and it’s not excluding – this is not an exclusionary criteria, I believe. It leans towards it. It makes it more likely that its drug induced, but it doesn’t make it impossible for any other cause to be considered.” He continued, “In my mind, the relevance of the previous diagnosis is that should lean more towards a diagnosis of a major mental illness and schizoaffective disorder being the cause of his presentation and the fact that – I was of that opinion because I started him on the Epilim to treat such a condition weeks prior to that.”

139. Dr Malik was asked to consider the cause of Luke’s psychosis on 1 April 2017, and he responded, “I think it was multi-factorial. I think drugs did contribute. However, I also think that his underlying mood disorder made things worse and also contributed to the number of episodes and how easily he became psychotic and how long he stayed psychotic.”

140. Dr Malik was asked his opinion as to why Luke may have decided that he didn’t want to continue receiving treatment from Dr Malik after his discharge from the Kiloh Centre. Dr Malik commented that “It could indicate an ongoing psychosis or a belief that I was part of the conspiracy against him. I also noted in the clinical notes that I read in the break that he said that he didn’t have enough money to afford an appointment and that could be the other reason why he wasn’t willing.”

Dr Malik was asked whether a person could be detained if the symptoms of the psychosis had settled but there was an underlying mental illness such as a schizoaffective or bipolar disorder. Dr Malik commented that “Yes, it comes under ongoing condition provisions. So an ongoing condition can be enough reason to detain someone when they’re not presenting as unwell currently and you would have to justify and say the ongoing condition could deteriorate and I’m holding them under that ongoing condition of bipolar schizoaffective.”

142. Dr Malik concluded his evidence by stating, “If Luke jumped off the Gap, he would’ve been mentally ill enough to make a decision to jump off the Gap. I don’t think a mentally well Luke would jump off the Gap.” Evidence from the conclave of experts

143. Three experts provided reports and attended court and gave oral evidence on 26 July 2023. The three experts were, Dr Christopher Ryan, Dr Andrew Ellis and Dr Gerald Chew.

144. Dr Christopher Ryan is a Consultation Liaison Psychiatrist. He is also a Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Sydney and an Associate Professor at the University of NSW. Dr Ryan provided two reports in this inquest, dated 12 October 2020 and 1 November 2021.

145. Dr Andrew Ellis is a Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist. His main practice is as the Medical Superintendent of the forensic hospital. He is also a conjoint Associate Professor at the University of NSW. Dr Ellis prepared one report dated 26 March 2022.

146. Dr Gerald Chew is a Consultant, General and Forensic Psychiatrist. Dr Chew prepared one report dated 24 May 2023. Dr Chew’s report also provided an opinion on the issue of lisdexamfetamine. In his reports, Dr Ryan provided his opinion that the diagnosis of a drug-induced psychosis as the appropriate diagnosis for Luke’s presentation. He confirmed in his oral evidence that it could also be a long-term illness, such as a schizoaffective illness which was aggravated by amphetamine use.

148. Dr Ellis indicated in his report that the more likely diagnosis was an exacerbation of an underlying mental illness, schizoaffective disorder, although acknowledged that the differential diagnosis of a drug-induced psychosis was a possibility.

149. The experts noted that Luke appeared very keen to be discharged from the Kiloh Centre. Dr Ellis commented, “You have a patient who is expressing a preference for discharge and that’s also important to take into account. You also have a patient who is expressing a willingness to engage in voluntary outpatient treatment and that’s also something important to take into account. And the information available to the Kiloh Centre at the time they made the decision to discharge is very different to the information that I’ve had available to me. So, if there was more information available to the staff at the Kiloh Centre, I do think that there would have been some cause, particularly, for example a discussion with Dr Malik about his concerns about Mr Huggard. So certainly, I think on the information available, the decision to discharge is not an unreasonable one. But I think that there probably – they are, I think, probably some things that could improve the discharge plan, as I’ve mentioned, about family and then other services who are going to take over his care once he’s discharged because regardless of diagnosis, whether he’s got a drug-induced psychosis or whether he’s got an exacerbation of his underlying disorder that he’s had documented for the past seven years, you would want there to be some follow up and so I think that that’s there. The other is that even with the best follow up, you may not prevent adverse outcomes, I think is another thing to be clear that it’s not necessarily going to prevent an adverse outcome, merely reduce the propensity for that to occur.”

Dr Ellis indicated that in his view the treatment plan should have had the involvement of Luke’s family, together with information for the family to enable them to provide additional supports. He also expressed the view that there needed to be community services support. He noted that Luke hadn’t met the substance use treatment service nor the transition to care team (TCT) at the time of his discharge. He further noted that ideally you would involve past cares such as ACON and his private psychiatrist.

151. Dr Ellis and Dr Ryan commented on the provisions of the Mental Health Act and the need to identify a designated carer. Dr Ryan commented on a situation where a patient refused to allow contact with a family member and the need to ask the patient further questions as to why they did not want the family member included or contacted.

152. Dr Ellis and Dr Ryan agreed that the responsibilities under the Mental Health Act fall to the authorised medical officer, however, those responsibilities can be delegated within the treating team. Both experts indicated that the system of delegation varied between facilities, however, it was ultimately the responsibility of the authorised medical officer.

153. Similarly, both Dr Ellis and Dr Ryan regarded the use of facsimile machines as being notoriously unreliable. In relation to the unsuccessful attempt to obtain further information from the Hills Clinic the experts felt again that “it’s the authorised medical officer’s responsibility to make sure that someone on the team” is following up with the request. They both agreed that “If it’s time consuming and futile to try and extract the information, you’re going to have to make decisions based on what you have at the time and you can’t detain people for what ifs.” They did note that the records had been outstanding for a number of days and it would not have been unreasonable to have followed up with an enquiry.

The experts were asked about their view of Dr Malik’s suggestion that section 14 (22) of the Mental Health Act could have permitted the ongoing detention of Luke from 4 April 2017. Dr Ellis indicated that it was possible, however, you need to “establish that that’s the least restrictive, safe and effective means” and that there were no other means of managing him in the community. He further noted, “So I’d agree with Dr Malik’s characterisation of it is that it gave an option for detention, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that you must detain, particularly if you have a suitable community treatment for the person.” Dr Ryan was of the view that it would be difficult “to come to the view on reasonable grounds that continuing to detain Mr Huggard in that circumstance was the least restrictive alternative for safe and effective care that was reasonably available in looking at his entire presentation and where apparently he was then and his apparently confident desire for discharge.”

155. In his expert report, Dr Chew was of the opinion that the prescription of Lisdexamfetamine by Dr Malik was appropriate in the circumstances. He confirmed that his opinion had not changed.

156. Dr Chew was asked to comment on the presentation and effects of patients who have ingested methylamphetamine versus lisdexamfetamine. He stated, “In my experience, it’s vastly different. So, in my experience, it’s quite common for people to present with psychotic symptoms and with methamphetamine doses but exceedingly rare for people to present with psychotic symptoms using prescribed doses of lisdexafetamine.” 157. Dr Chew was asked if a patient had ingested in excess of their prescribed dose, could that potentially cause a drug-induced psychosis. Dr Chew commented, “I think it could potentially cause psychotic symptoms, yes”.

Dr Chew was asked whether one could discern which drug was used and he responded, “I think it’s very difficult to determine if it was the lisdexamfetamine albeit maybe taking the higher doses or the illicit methamphetamine. But just with clinical experience, I would think it would be more likely to be the methamphetamine to be honest.”

159. Dr Ryan was asked if Luke did jump from the Gap, was it reasonable to assume that he was still unwell at the time of his discharge from Kiloh Clinic. Dr Ryan stated, “I mean, I think that’s a possibility. A possibility is that he took some more amphetamines, which has got to be another fair possibility. I wouldn’t want to try and rate between those two.”

160. Dr Ellis was asked whether the decision to discharge Luke was appropriate. Dr Ellis indicated that it was and then further elaborated that the Kiloh Centre did not have the benefit of a number of health records referred to in these proceedings. He stated, “I think that there would’ve been a significant reconsideration of the discharge plan if all that information was laid before you. I think, firstly, I had a significant difference of opinion with some of my colleagues who report that they can, by their cross-sectional examination, tell the difference between schizophrenia and drug-induced psychosis. It’s incredibly difficult to do”.

161. He continued, “I think that, in particular, that he had the previous month been admitted for several days to the Hills Clinic where psychotic symptoms are diagnosed and he’s not taking drugs. And this is – now it may be that he’s got one of these rare drug-induced psychoses that lasts for months. But this is also a man that’s been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder five years prior. At another admission, he’s been also diagnosed in the United States after a several month admission to a rehabilitation. I think that the weight of evidence is that this man has a major mental illness and it’s been exacerbated by drug use. And relying on your own clinical impression, no matter how experienced you are, my experience tells me not to rely on my experience. Okay? That you need to, you know – if you’re going to be more as definitive as saying this is a drug-induced psychosis because I’ve seen lots of cases, it’s actually, I think, the reverse. The more cases you see, the more sceptical you should be of your own clinical impression there. So I think if you had all that information, there would’ve been a significant revision of decision-making about his care. But that being said, it wasn’t there for various reasons.”

162. Dr Ellis further noted, “I would be erring on the side of looking at the longitudinal picture rather than the two days that I’d seen the patient and he was unwell one day and then the next day he was well because there is natural fluctuation in psychosis. Even people with chronic schizophrenia will have periods of lucidity where they, for all intents and purposes, will be undiscernible from the rest of the population.

163. He continued, “So you need to take the long picture into account I think much more than was perhaps – I would take a different approach to my colleagues who discount that longitudinal picture. I think that longitudinal picture is pretty indicative. But they didn’t have the same amount of time that I had to read all those notes and they didn’t have all the notes that I had, and they’d seen him for a much briefer period of time. So, I don’t criticise them for making a diagnosis of drug-induced psychosis. But with all my information, I think it’s less likely.” Dr Chew was asked for his views. He stated, “I agree, and I think in my report I gave my opinion that I – that in my review of all the material that I was provided with pointed to the most likely diagnosis being schizoaffective, one underlying major mental illness being exacerbated by drug use. I agree with Dr Ellis’ comments.”

165. Dr Ellis returned to the issue of not notifying Luke’s father and expressed concern that the issue was not further ventilated, particularly given the earlier threats to his father at the time of his admission. Dr Ellis indicated that you would want to ensure that those delusions relating to his father had resolved before discharging Luke. Dr Ellis noted that you may wish to consider a different form of discharge, which involved a much more assertive, community-based plan.

166. Dr Ryan stated, “I find it hard to believe that there wasn’t – well, we know that Mr Stephan Huggard was mentioned because there’s a line in the notes that refers to him. So there’s some sort of conversation that happened, I can’t imagine why you wouldn’t, in that circumstance when he says “I don’t want my dad notified”, that you wouldn’t ask why you don’t want your dad notified because there’s so many reasons I want to know the answer to that question”.

The evidence of Ms Sharon Carey

167. Ms Sharon Carey was the General Manager of Mental Health Services at South Eastern Sydney Local Health District (SESLHD) from February 2022 until July 2023. On 18 July 2023, Ms Carey commenced in the role of General Manager Corporate Services at the SESLHD.

168. Ms Carey prepared two statements dated 24 April 2023 and 25 July 2023 for these proceedings.