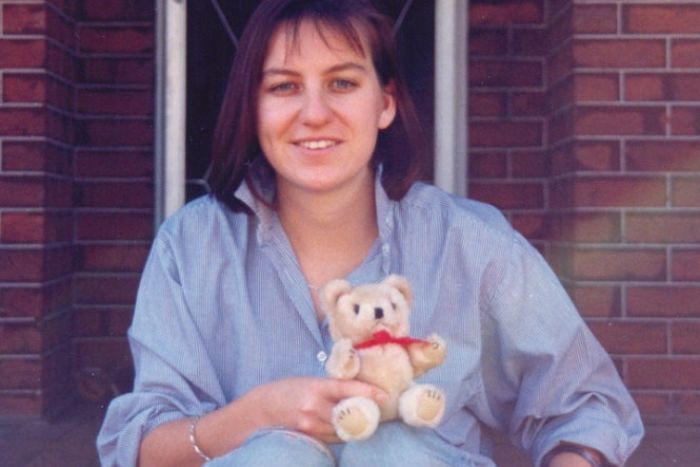

Julie Leanne CUTLER

DESCRIPTION:

BACKGROUND:

Julie Leanne Cutler was 22 years of age at the time of her disappearance. She enjoyed reading, writing and socialising with friends. She was working casually at the Parmelia Hilton Hotel in Perth WA as a room attendant and lived in Fremantle with a female flat mate.

CASE DETAILS:

On the evening of Sunday 19 June 1988, Miss Cutler was working at the Parmelia Hilton Hotel, 14 Mill Street, Perth. After finishing her shift, she attended a staff awards night at Julianna’s night club, which was part of the Parmelia Hilton. It is believed that around 180 people attended this function until around 12.30am on Monday 20 June 1988.

Miss Cutler and a female co-worker left the work function, walking together to the staff parking area of the hotel. Miss Cutler was seen by her co-worker bending into the open front passenger side door of her car. Miss Cutler’s car was a two-tone grey and black Fiat sedan registered number 6CW749. It is believed that Miss Cutler then re-entered the hotel and function until it finished, before returning to her vehicle and driving away. The Fiat sedan was last seen turning left from Mill Street onto Mounts Bay Road.

Miss Cutler did not arrive home in Fremantle that night and did not attend work at the hotel for her rostered shift later that day.

In the morning of Tuesday 21 June 1988 Miss Cutler’s flat mate reported her missing.

VEHICLE LOCATED:

About 11.45am on Wednesday 22 June 1988, Miss Cutler’s car was located several metres off the shore-line at Cottesloe Beach by a swimmer. The car was about half way between the Surf Life Saving Club and the groyne. At this time the car was upside down, half buried in the sand. The rear seat of the vehicle was located separate to the vehicle.

The person or persons responsible for Miss Cutler’s disappearance have not yet been identified.

REWARD:

On 19 June 2018, the Government of Western Australia announced a $250,000 reward for information which leads to the apprehension and conviction of the person, or persons, responsible for Julie’s disappearance.

The Government may also be prepared to consider recommending a protection from prosecution, or pardon for any informant with information that leads to the conviction of the person or persons responsible for the disappearance, provided that the informant was not directly responsible for the disappearance of Julie Cutler.

If you have any information about the disappearance of Julie Leanne Cutler, please contact Crime Stoppers on 1800 333 000 or make an online report below. Please remember that you can remain anonymous if you wish and rewards are offered.

CORONER'S COURT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA :

CORONERS ACT 1996 :

SARAH HELEN LINTON, DEPUTY STATE CORONER :

3 - 4 NOVEMBER 2022 : 6 APRIL 2023 :

CUTLER, JULIE LEANNE

RECORD OF INVESTIGATION INTO DEATH

I, Sarah Helen Linton, Deputy State Coroner, having investigated the disappearance of Julie Leanne CUTLER with an inquest held at the Perth Coroner’s Court, Court 85, CLC Building, 501 Hay Street, Perth, on 3 and 4 November 2022, find that the death of Julie Leanne CUTLER has been established beyond all reasonable doubt and that the identity of the deceased person was Julie Leanne CUTLER and that death occurred on or about 20 June 1988 at Cottesloe Beach or elsewhere as a result of an unknown cause in the following circumstances:

INTRODUCTION

Julie Cutler was last seen alive in the early hours of the morning on 20 June 1988. She left a work function at the Parmelia Hotel in the city, got into her Fiat sedan and drove away. Julie was seen turning onto Mounts Bay Road by a work colleague who was waiting for his ride home. Two days later, Julie’s car was found in the ocean at Cottesloe Beach, approximately 50 metres from the shore. The car was empty.

An extensive search was undertaken of the area, but Julie’s body was never found. From the outset, there was a strong suspicion that Julie was deceased (although the possibility that she was still alive could not be ruled out entirely). As to how she was thought to have died, it was unclear to police whether her suspected death involved an act of suicide or if another person or persons were involved. Julie disappeared at a time when the small town of Perth had recently been rocked by the abductions and subsequent deaths of a number of young women at the hands of David and Catherine Birnie.

A number of years after Julie’s disappearance, three other young women also disappeared in suspicious circumstances, namely Sarah Spiers, Jane Rimmer and Ciara Glennon. The bodies of Ms Rimmer and Ms Glennon were subsequently found and they were later proven after trial to be the victims of the Claremont serial killer, Bradley Edwards. There remains a strong suspicion that this was also the tragic fate of Ms Spiers, although her body has never been found and no conviction has been recorded. At the time of Julie’s disappearance, these latter cases had not occurred, but over time it was suggested that there could be a connection, given some similarities between those other three young women and Julie and the circumstances in which they first disappeared. However, evidence before me now suggests that there is unlikely to be any connection and this is consistent with her father, Mr Cutler’s, understanding from police.1

Julie’s disappearance has been the subject of extensive investigation by the WA Police for more than three decades. It has been the subject of much media attention and public interest, but no witness has ever come forward to say that they saw Julie or her car enter the ocean at Cottesloe Beach, or to provide specific information as to how or why Julie disappeared. Julie’s family and friends have come to accept that she is no longer alive, but are still hopeful they might one day find out what happened to her. In November 2017 the Cold Case Homicide Squad commenced a review of all the evidence already obtained by police, and then conducted extensive further investigations into Julie’s disappearance and suspected death. Their investigations continued throughout 2018, with considerable efforts made by police to track down old witnesses and follow any new leads.

When the investigation, codenamed Operation Malvae, was completed in February 2019, the investigators concluded there were two possible scenarios open in regard to what happened to Julie:

• Julie was murdered between 20 and 22 June 1988 and the person or persons responsible ensured Julie’s vehicle entered the water at Cottesloe Beach; or 1T 21. Page 3 [2023] WACOR 19

• Julie took her own life between the early hours of 20 June and 22 June 1988, deliberately driving her vehicle into the ocean at Cottesloe Beach and drowning at or near that location. 6. 7. 8. 9.

A detailed investigation report was prepared and provided to the State Coroner in February 2019, setting out the reasons why the police suspect that Julie is deceased and the evidence that supports the two possible conclusions as to how she met her death, as set out above. On the basis of the information provided by the WA Police in relation to Julie’s disappearance, Acting State Coroner King determined that pursuant to s 23 of the Coroners Act 1996 (WA), there was reasonable cause to suspect that Julie Cutler had died and her death was a reportable death. He therefore made a direction that a coroner hold an inquest into the circumstances of the suspected death.2 I held an inquest at the Perth Coroner’s Court on 3 and 4 November 2022.

The inquest consisted of the tendering of documentary evidence compiled during the police investigation conducted into Julie’s disappearance, as well as hearing evidence from a senior police officer involved in the recent cold case investigation, some key witnesses who had contact with Julie prior to her disappearance and some of Julie’s family members and friends. An inquest is a-fact-finding exercise and not a method of apportioning guilt. In deciding the best way to conduct this inquest I considered the relevant evidence, issues and witnesses to be examined at the inquest hearing. Julie’s family and the Western Australian community can have the utmost confidence the investigation has been given closely scrutinised, both by the WA Police and this Court. I have given close attention to all of the documentary evidence before me as well as the oral evidence given by the witnesses who were called. In particular, I was assisted by the evidence from Julie’s family and friends as to the kind of person she was and whether they believed she might have made a choice to take her own life. They were all firm in their belief that Julie would not have committed suicide, but were not able to provide any evidence of any particular person who may have wished to harm Julie.

10. The WA Police Cold Case Homicide Squad investigation compiled a list of 48 persons who were classified as suspects, using the lowest level of suspicion as a baseline. At the end of the investigation 44 of those nominated as suspects could not be eliminated in Julie’s disappearance. Five of the nominated suspects had died prior to the 2018 investigation commencing and some other witnesses had died, as well as others not being in a state of health suitable for giving evidence.3

11. I note in particular that the inquest did not hear evidence from Bradley Edwards, who is currently incarcerated for the murders of Ms Glennon and Ms Rimmer and other offences. I was advised by WA Police that he has not agreed to participate in interviews since his convictions, but in a previous conversation he denied any knowledge of Julie Cutler. The investigating officers have concluded there is no compelling evidence to elevate him above the many other persons of possible interest. I note there has been a suggestion in some reporting that this inquest could have been an opportunity to call Mr Edwards and compel him to answer questions, contrary to his right to silence, on other matters unrelated to Julie’s disappearance and suspected death. With respect, such a suggestion demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of the powers of the coroner. I mention it only to ensure that the community is not left with the misapprehension that there was an opportunity lost for justice to be served for another family.

12. At the conclusion of the inquest, I indicated that I was satisfied on the available evidence that Julie is deceased, and she died on or about the time she disappeared on 20 June 1988. As for how Julie died, I am sadly compelled to leave her cause of death undetermined and to make an open finding as to her manner of death. I explain my reasons for those findings below.

BACKGROUND

13. Julie was born on 27 July 1965 in Perth and was the first child of her father, Roger Cutler, and mother, Robyn Cutler. Julie’s sister, Nicole Cutler, was born a year later. In the girls’ early years the family lived in Wembley and Julie and Nicole attended Brigidine Catholic Primary School in Floreat. Unfortunately, Mrs Cutler developed cancer and passed away on 3 January 1976. Her early death obviously had a lasting impact on her two little girls. Nicole recalled that their mother’s death came as a shock, as they had not been prepared for it, and both she and Julie were quite traumatised.4 Julie’s father recalled that Julie was “pretty well bereft”5 at the time, and there was mention in the evidence of how deeply it affected Julie even as an adult.6

14. Mr Cutler remarried in 1977 and moved to a home in Dalkeith. Mr Cutler and his new wife had four more children, Rachael, Rebecca, Alexander and Jessica, so Julie and her sister Nicole had four younger siblings. Julie’s father was away a lot for work and she did not develop a close relationship with her stepmother. She did have a very good relationship with her grandparents who lived in York, and visited them regularly.7

15. Mr Cutler described Julie as an easy child to parent. He remembered Julie as a “quiet, shy, reliable, introspective girl”8 who was respectful of other people, reliable and sensible.9

16. Nicole described Julie as “a really lovely person who would help people in need. She was a good, kind person with a great sense of humour.”

17. Julie and Nicole became students at Iona Presentation College in Mosman Park, where Julie remained until her graduation from high school in 1982. Julie was a good student who was well-regarded at her school by her teachers and peers. She was a voracious reader, and was very creative and loved to write. After finishing school, Julie attended the Western Australian Institute of Technology (WAIT) in Bentley, which is now Curtin University. Julie majored in English Literature and also studied Theatre Arts and Creative Writing with a minor in Psychology. At some stage during her university studies, Julie moved out of the family home in Dalkeith and into a house in Victoria Park that was owned by her family.11

18. Nicole recalls they were quite different, despite being sisters. Julie was the more grounded of the two of them and the ‘good’ one. Nicole described Julie’s personality as having two polarities: she was often quite reserved but could also be quite extroverted and adventurous at times. Julie was also very funny, kind and extremely honest. Nicole noted that Julie was quite a private person, who liked to keep some things to herself and to keep the different parts of her life separate, so they did not share everything that was happening in their lives. However, they were still sisters and cared about each other.12

19. Julie loved visiting the Fremantle Markets, where she later found work, and going to Cottesloe Beach, where she would sit in her car and watch the ocean.13

20. Julie was completely independent from her father in terms of her living expenses at the time of her disappearance. She worked as a waitress and at a dress shop at the Fremantle Markets while studying. Julie had got the job at the dress shop in Fremantle after being a customer at the store.14 She also received a student allowance and had a small inheritance from her mother.15

21. Julie had been working at the Parmelia Hilton Hotel in Mill Street, Perth, as a room service attendant while studying. A work colleague, Concetta Plati, recalled Julie was also working a part-time job at a bar at Perth Airport. Ms Plati remembered Julie as “a nice girl, very sweet”16 although she also remembered Julie saying, “I’m not your typical Catholic.”17 Ms Plati was aware Julie’s mother had died when she was quite young and that her father had remarried and had more children. Julie didn’t live with them or visit them often. Julie was close to her sister Nicole and was very fond of one of her half-sisters and spoke about her often.18

22. Julie had a close friend, Jennifer Marr,19 who studied Theatre Arts with her at WAIT. Julie had first met Jennifer at a theatre arts workshop when they were 14 years old,

23. I refer to Jennifer Marr as Jennifer in this finding to avoid confusion with her sister, Fiona Marr, whom I also refer to later in this finding. but they got to know each other better when they were studying at university together and became very good friends. Julie also became very close to Jennifer’s family as a result of their friendship, and felt herself to be part of the Marr family. Julie and Jennifer studied together, worked on theatre and film productions together and would also socialise together. Jennifer recalled Julie rarely smoked and the only drug she ever used was cannabis, which was also rare. Jennifer recalled Julie would mostly drink white wine or champagne. Julie got drunk easily, and was usually happy and extroverted when she had been drinking, although on occasion she would experience bouts of depressive emotions when drinking. As well as spending time together, Julie and Jennifer would often go out with a large group of friends who were also studying Theatre Arts and working in the industry, including both girls and boys.20 23. Jennifer described Julie as “[v]ivacious, fun-loving, intelligent, creative, very extroverted at some times,”21 but her external persona was also balanced by a more reflective, quiet inner person. Julie loved socialising and they spent many nights out together in Claremont in the pubs and nightclubs, as well as parties at home. Jennifer remembered that Julie enjoyed having a drink, but could also have a good time without drinking. She loved to dance and enjoy herself and Jennifer remembered Julie as generally happy, whether or not she was drinking. However, Jennifer also recalled that Julie was “known for moments of drama”22 and she could take things to heart and blow things a bit out of proportion at time.23

24. As good friends, Jennifer and Julie would often confide in each other, and Jennifer was aware that Julie had been deeply affected by the loss of her mother but she also was very respectful of her remaining family and always spoke of her father, sister and other siblings affectionately.24

25. Julie was in a brief sexual relationship with another WAIT student, Peter Docker, who was dating her friend, Rebecca. Julie had known Mr Docker for a number of years and they were friends. He was aware that Julie also slept with other men, some of them strangers. Mr Docker described Julie as a “troubled girl who was quietly spoken but with a good sense of humour.”25 She dressed quite conservatively and had excellent manners. She was also a very honest and loyal friend.26

26. Julie finished her studies and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in February, 1986. Julie had saved up her money while studying and she went travelling overseas in mid-1986. She travelled to Greece, France and the United Kingdom. Julie and Jennifer kept in contact by letter while she was away and she was aware Julie found work as a nanny au pair for a family and travelled with the family, and she also visited Jennifer’s elder sister who was living in London at the time.

27. Mr Cutler recalled Julie calling him from Greece and telling him that she had experienced a problem with a man and he had hurt her. One of Julie’s friends from WAIT, Rebecca McDonald (formerly Bateman), provided information in her statement to police that Julie had met a man in Greece and she had warned Julie to be careful as she was concerned “he may just be trying to rip her off.” Julie did not heed the warning. One night Julie rang Ms McDonald and was hysterical, asserting that the male had robbed her. It seems he did not, in the end, steal anything from her, although the relationship did end. Julie reacted badly and when Ms McDonald went to where Julie was staying, she found Julie had cut both her wrists and her room was full of blood. Julie had to be taken to hospital for treatment.

28. In her travel diary, Julie referred to a man called ‘Yoros’ show she alleged drugged her drink with the intention of having sex with her.

29. Ms McDonald later told police in her statement she had “always thought there was a blackness” about Julie and she felt Julie “always appeared troubled in some way.”

30. Jennifer spoke to both Julie and Ms McDonald about the incident in Greece afterwards. Jennifer recalled it seemed to have been a very dramatic sort of incident that occurred when Julie had been drinking. It was not something that she had ever seen or heard Julie do or say before. Jennifer knew Julie to be someone who had been brought up with strong values and to try to hurt herself was not consistent with her family background or her values. Julie had never spoken of suicide and Jennifer gave evidence she was shocked when she was told about the incident in Greece, and she believed Julie and Ms McDonald were also shocked by it.

31. Julie later wrote about the incident in Greece in her diary and its clear

the relationship ended that night and she found the incident very distressing.

After this incident, Julie left Greece and returned to the United Kingdom, where

she apparently had another boyfriend. This relationship appears to have been a

more stable one and the boyfriend came to Perth to help with the search for

Julie after she disappeared.38 There were the relationships with the male in

Greece and a boyfriend called John in the United Kingdom, and also the brief

interlude with Peter Docker, who was Ms McDonald’s boyfriend and had been at

university with Julie. Ms McDonald referred in her statement to having “cleared

the air with … Peter and Julie about what had happened between them”39 and it

seems there was no relationship between Mr Docker and Julie after she had

returned to Perth from her travels.40

JULIE’S RETURN TO PERTH 1987 - 1988

32. When Julie returned home in late 1987, she lived for a short time in the house in Victoria Park again. Her sister Nicole was also living there by that time. Julie later moved out, around January 1988, and moved in with her friend Jennifer’s older sister, Fiona Marr. They lived together in a Unit 19/10 Stirling Street in Fremantle.41

33. Julie had owned a number of cars, the last one being the Fiat. She had bought the Fiat on her return to Perth following her overseas holiday. Mr Cutler remembered there was a problem with the front driver’s side door and it wouldn’t open, so Julie would have to enter the car from the passenger side. He couldn’t remember if the problem was only with opening the door from the outside and whether the door was able to be opened from the inside or not.42

34. Julie did not see her father regularly as he often worked overseas or in other parts of the country. She did write to him or call him occasionally. Mr Cutler believed Julie was closest to her maternal aunt, Annette Marwick, and her grandmothers on both sides. She was also close to her stepsister Rachael and a friend from school. He was not aware of the names of any of her boyfriends, although he assumed she had them and he was aware of the former boyfriend who came over from the United Kingdom to help search for Julie after she disappeared. There is evidence on the brief to indicate that boy was John Gilbert, who had met Julie in England and had moved back to Australia in the eastern states at the time Julie went missing. Julie’s father did not know of any current boyfriend or girlfriend at the time she went missing.43

35. Ms McDonald, who had studied with Julie and been with her in Greece, had reconnected with Julie on her return home to Perth. She told police she would socialise with Julie, together with other friends, regularly. Ms McDonald did not recall Julie having a permanent partner. She recalled that Julie was otherwise very private and would not usually talk about her boyfriends with her friends. Ms McDonald did recall Julie mentioned, about a month before she went missing, that she was gay or bisexual, but they did not discuss it further. Ms McDonald did understand Julie had been in a long term relationship with a female friend from school, which had ended prior to her starting university. However, Ms McDonald only ever saw Julie with men.44

36. Julie had also told her close friend, Jennifer, in early 1986 that she believed she was gay and that she had been in a relationship with a friend at school. Jennifer was aware that Julie had strong religious views as a result of attending a Catholic school, and felt Julie may have had difficulty coming out as gay given her background. However, Ms Marr was also surprised by the information as she was aware Julie dated men and sometimes would engage in intercourse with them. Ms Marr was aware that Julie had dated Peter Docker briefly and also went out with another male named Martin, as well as having short lived interactions with other men she met.45

37. Julie’s sister was aware that Julie had a close relationship with another student in high school, that was likely more than friendship, but she believes Julie and the friend drifted apart after Julie started university.46 and there is no mention of her in later years. In the months they were living together in 1987, Julie did not bring anyone home to the house they shared.

38. Both Ms McDonald and Jennifer Marr were aware that Julie became pregnant in 1986, before she went overseas, and arranged to have a termination as she felt she was not in a position to care for a child at that early stage in her life. Ms McDonald recalled Julie was very upset at having the procedure, as did another friend, whereas Jennifer recalled Julie knew it was the right thing to do, given how young she was, and therefore was realistic about the decision. It does not appear that she spoke to anyone further about this decision after her return to Perth, so it does not seem to have continued to prey upon her mind.47

39. Jennifer said that Julie was generally level headed but she could be unpredictable and occasionally depressed. She told police that Julie was known to be a “drama queen” and sometimes this was fun, but it could also be excessive. Julie appeared to suffer from some “deep seated and persistently negative thoughts where minor incidents would cause her to react or go into her shell.”48 Her friends would often ignore these changes of mood as they thought she was attention seeking. Both Ms McDonald and Jennifer recall Julie appearing to engage in what they described as “promiscuous”49 and “risk taking behaviour,”50 where she would meet a man while out and have sex with him on the same evening.

40. On 31 December 1987, Jennifer recalled celebrating New Year’s Eve with Julie in Fremantle. It was not long after Julie had returned home to Perth from her overseas trip. It seemed to Jennifer that Julie was having difficulty settling down at home after her travels and she believed Julie was a bit depressed about being home and returning to work as a waitress.51 Jennifer, who appears to have been Julie’s closest friend at this time, went overseas in March 1988 so she was not socialising with Julie in the months leading up to her disappearance.

41. Julie’s sister had also felt Julie struggled to settle back into the routine of life in Perth after her travels.52 Nicole was not in contact with Julie in the months leading up to her death. When they were living together in Victoria Park they had been getting on well but then they argued and Julie moved out at the start of 1988. The argument was very sudden and Nicole could not recall what it was about, other than Julie called her ‘selfish’. Nicole remembers Julie got really angry and stormed off to the service station, hired a trailer, then came back to the house and moved out immediately. Reflecting back on it now, Nicole thought it might have been because Nicole and her friend had moved into the house while Julie was overseas and Julie probably didn’t want to be living with her sister after being away, and wanted more independence. They did not see each other again until shortly before Julie disappeared.53

JULIE’S MENTAL STATE PRIOR TO HER DISAPPEARANCE

42. In 1988, Julie was working at the Parmelia Hotel in Mill Street, Perth, as a room service attendant and also at the dress shop at the Fremantle Markets. Ms Wilkes, who employed Julie at the dress shop, remembered Julie dressed conservatively and was a “good, nice, ordinary girl”54 who was always smiling and happy and easy to get on with. Ms Wilkes was asked by police some years later about what handbag Julie had at the time she disappeared, and Ms Wilkes recalled drawing a brown natural leather bag for them.55

43. The last time Julie saw her father was at a family dinner at an Italian restaurant in Northbridge. At that time Mr Cutler, his wife and the younger children were moving to Kalgoorlie. Mr Cutler believes this was between three and six months before Julie disappeared. Julie seemed fine during the dinner and there was nothing out of the ordinary about the night.56

44. Julie called her father about a month before she disappeared and he recalled they discussed something that happened involving a car possibly following her on Stirling Highway on her way home from work, although he could not remember the details of the incident. Around this time, Julie also had a discussion with her father about coming to Kalgoorlie to visit. The plans were for Julie to go and visit sometime in late June or early July 1988, but she went missing a couple of weeks before this could occur. Julie had also rung her grandmother in York to ask if she could come and stay. Julie was always welcome there, but she did not make it to York either before she disappeared. Mr Cutler wondered later if Julie had been wanting to have a talk about something with him or her grandmother, but he wasn’t aware of anything in particular concerning her.57

45. When Julie’s flatmate Fiona reported her missing to police, she told them that Julie had been concerned about a language course she wanted to undertake at Milner International College of English to qualify for teaching English as a second language. Apparently, Julie had been told she could not keep her employment as a waitress as well as study and Julie was upset as she could not afford to do it. Fiona recalled the course was very intensive and Julie had been told she had to be there fulltime, 9 to 5, which she couldn’t do at the same time as her job at the Hilton, which she needed to keep the money coming in. Fiona remembered Julie was downhearted about having to give up the course, but Julie was a private person and didn’t confide much in Fiona.58

46. Ms Valma Granich, who was the Director of Teacher Training for Milner College at that time, told police that Julie had enrolled in a month long Intensive English course but she pulled out shortly before she was due to commence. Ms Granich explained that Julie had come to see her and they had spoken about Julie’s circumstances and the intensive course she had enrolled in. Ms Granich recalled Julie was highly emotional and crying. She mentioned she had no support network and her mother had died. Julie also said she was a bit unsettled after recently coming back from travelling overseas. She was living with a friend and was financially strapped while working part-time.59

47. Ms Granich explained to Julie that due to the demanding nature of the course, working at all during this time would not be possible. Ms Granich suggested that Julie would do better to do a later course, and assured her that she had a definite place in their next course if she felt more settled financially and emotionally by that time. Ms Granich believed Julie felt better after their discussion. It was usually the College’s policy to not completely refund money for courses if the candidate was unable to attend, but due to Julie’s circumstances and the fact that another student filled her place, the College made an exception to the policy and decided to give her a full refund. A letter with the refund cheque was posted to Julie on or about 17 June 1988, so it seems she would not have received it before she disappeared and it is possible she was unaware she was getting the full amount she had paid refunded.60

48. However, a friend of Julie’s, Gregory Cowan, who was aware that Julie was deliberating about doing the course and was concerned she could not afford it, recalled that she was not overly concerned about it before she went missing. He spoke to Julie at about midday on the Sunday, shortly before she disappeared, and at that time she told him that she couldn’t go into the course because the place had been filled.61

49. Fiona Marr also told police Julie had not been in a stable relationship for six months.62 Julie saw a doctor on 13 June 1988 at Fremantle Medical Centre. Information from the medical centre suggested it was a routine appointment and there was nothing of concern raised at the time. It seems she had recently come off the pill, which supports the other information that she was not in a steady relationship at the time.63

50. Information provided to the Missing Persons Team indicated Julie was in good health but there was some suggestion she may have been depressed at or around the time of her disappearance.

51. Ms Wilkes recalled Julie worked at the shop the Friday night before she disappeared on the Sunday, and she did not remember anything out of the ordinary when she handed over to Julie at the start of her shift on the Friday afternoon. She recalled being shocked when she heard about Julie’s disappearance and the discovery of her car in the ocean only a few days later.65

52. Julie’s friend, Ms McDonald, recalled an incident about a month before Julie went missing. They were having drinks at Ms McDonald’s parents’ house in Peppermint Grove before they headed out to Club Bayview in Claremont. Julie apparently made reference to being gay or bisexual and reportedly made some strange comments, such as “I’m not for this life.”66 She was also seen to flirt with some men that night after she had been drinking. Ms McDonald recalled that Julie “could be quite crazy after drinking”67 and when intoxicated she would sometimes be “promiscuous.”68 However, like Julie’s father, Ms McDonald did not recall Julie being an illicit drug user.

53. Julie’s work friend, Ms Plati, had left the Hilton by the time Julie returned to work there but they did meet up once to socialise before her disappearance. Ms Plati had dinner with Julie, Eveline and two other girls from the Hilton. The dinner was only a few weeks before Julie went missing. They went to Subiaco and Ms Plati remembered seeing Julie get out of her car, a Fiat, on the passenger side. Julie commented that it was a nice car except that she had to get out on the passenger side. Ms Plati remembered that during dinner Julie seemed fine and quite cheerful. She told stories about her holiday and nothing seemed out of the ordinary. Ms Plati believed that Julie had mentioned having a boyfriend, but did not know any details other than she had the impression it was a long distance relationship.69 After their dinner, Ms Plati did not have any further contact with Julie.

54. Julie had moved in with Fiona Marr in order to share living expenses. They had different social circles and worked at very different times, so they did not socialise much together. However, just from her experience of them living together, Fiona came to know Julie as someone who was a “dramatic person”70 and also someone who was very private and “at times quite moody.”71 Fiona attributed this behaviour to Julie’s early loss of her mother and troubled relationship with the rest of her immediate family. Fiona also remembered Julie as very witty and intelligent. Fiona was aware that Julie would drink to excess at times and she worried that, when intoxicated, Julie was placing herself at greater risk without much thought. She gave examples of Julie hitchhiking and associating with people she didn’t know, including having one night stands or going to remote and isolated locations with a stranger. Julie would hint at having some of these experiences, but did not tell Fiona much detail.72

55. Jennifer had left to travel to Japan in March 1988 and while they did not see each other from that time, Julie and Jennifer wrote letters and postcards to each other. About three weeks before Julie went missing, Jennifer received a postcard from Julie with a picture of Marilyn Monroe on the front. On the back of the card, Julie wrote, “I wish I could be sucked off the face of earth by a delicious dose of cancer.”73 Jennifer did not keep the card but she still recalled she was shocked at the statement as she knew Julie’s mother had died from cancer and she thought what Julie had written on the card was “inappropriate, negative and dramatic”74 and was disappointed with her for sending it.75

56. After Jennifer was informed by her sister Fiona that Julie was missing, Jennifer reread all of Julie’s letters to her and recalled that “[n]one of the letters were very uplifting and there was only one letter that was really positive.”76 Jennifer realised after re-reading them all that Julie was not in a good head space at that time when she wrote the letters. After Jennifer was informed that Julie was missing, she made a note in her travel journal on 28 June 1988 referring to the letters and acknowledging that in hindsight, they were probably a “cry for help”77 that Jennifer had unwittingly ignored.

57. However, Jennifer had also spoken to Julie on the telephone on 13 June 1988 from Tokyo and there had been a different tone to the conversation. Jennifer had rung her sister Fiona to wish her a happy birthday, and spoke to Julie at the same time. Jennifer recalled the phone conversation was quite upbeat as Jennifer was excited about being in Tokyo and also because it was her sister’s birthday, so she recalled it was a fun and lively conversation.78 Fiona also remembered the conversation was upbeat between the three of them.79

58. Jennifer told police that she “did not believe that Julie was mindful of her safety before she went missing. She was not making wise decisions and [Jennifer] did not think she was 100 per cent happy within herself.”80 However, she had never heard Julie say anything about wanting to commit suicide.

59. Jennifer was aware in a letter sent to her by Julie that Julie had been in some kind of relationship with a man called ‘Idris’, or something like it. She recalled that Idris had wanted Julie to travel to Morocco with him and Julie had declined. Jennifer believed Julie had met Idris through work. Other than mention of him, Jennifer did not recall Julie mentioning being in a relationship with any other person prior to her disappearance.81

60. Jennifer’s sister, Fiona, also was aware of a man called Idris and another man called something like Hiams, but she did not have a strong recollection of Julie having any permanent partner while they were living together.82

61. Nicole had not spoken to Julie since she had moved out after the fight in January 1988. Nicole went to see Julie at her job at the Fremantle Markets sometime in June 1988 to try to reconnect with her. Nicole didn’t have Julie’s phone number, so she had gone to visit her in person to ask her if she would come and have a cup of tea and try to sort out their argument. They spoke briefly and Julie told Nicole she would call her to arrange to meet up. Nicole had felt good after their chat and had no reason to believe Julie wouldn’t call. However, Julie had not called to arrange the meeting before she went missing.83

62. Of particular significance is a conversation Julie had with a work colleague, Carmela Fleming, on the night of Saturday, 18 June 1988, shortly before her disappearance. Ms Fleming was the Head Waitress of the Banquet at the time and Julie had been sent to assist her at a private function being held in the penthouse suite on the 10th floor of the hotel. Ms Fleming recalled that Julie kept opening the sliding doors to the balcony and stepping outside. From the balcony, you were able to look down to the carpark. Ms Fleming said she was getting angry as she wanted Julie to stay inside and help her with the function, but Julie continued to go outside and wouldn’t tell her the reason. Ms Fleming also recalled that Julie seemed upset and said words to the effect, “I just want to jump, I just want to kill myself.” Ms Fleming did not respond and simply asked Julie to come back inside to assist her with serving the guests.

63. At the end of the night, when they were cleaning up, Julie finally told Ms Fleming that she had broken up with her boyfriend and she wondered if his car would be in the basement, so she kept going outside to check.84 Ms Fleming recalled that Julie became very upset and could not stop crying. Ms Fleming attempted to console Julie by telling her she was young and had lots of fun ahead of her, but did not ask any further questions. At the end of their shift they both walked to their cars. Ms Fleming recalled Julie seemed calmer by that time and she got a dress from her car and walked back inside the hotel while Ms Fleming drove away. Ms Fleming did not have any further contact with Julie after that night, although she did hear about Julie’s car later being found in the ocean.85

64. Fiona saw Julie on the morning of Sunday, 19 June 1988. Fiona did not recall anything out of the ordinary in Julie’s behaviour, although she acknowledged that Julie did not really confide in her. Julie was still at home when Fiona left the unit to go out with a friend. Julie was not at home when Fiona returned later that afternoon and it appeared she had gone to work. Fiona did not see Julie again.86

65. Before she left for work on the Sunday, Julie had a phone call with Gregory Cowan at about midday. As well as discussing the English course, as detailed above, Mr Cowan recalled that he told Julie he might be in Fremantle on the coming Tuesday night and might come to see her. Julie told him she didn’t know if she would be home or not, so he should ring her first. Mr Cowan also asked Julie if she wanted to go with him to the Subiaco markets that afternoon. Julie told him she was watching some old movies on the television and didn’t want to go out. Mr Cowan told police he had known Julie to get depressed on a few occasions, but not for any particular reason. He remembered her as generally a “dramatic but happy person.”87 Julie and Mr Cowan had dated in the past and had remained friends after their relationship ended. He knew she had dated other men after their relationship ended, but they did not discuss it much and he wasn’t aware of anyone Julie was dating at that time.88

66. Julie’s aunt, Ms Marwick, also spoke to Julie on the Sunday, a little before lunchtime. She recalled Julie was cleaning out the cupboards and she mentioned she was going to work later and that there was going to be a party and presentation for the Parmelia staff that night. At that stage, Julie told her aunt she wasn’t sure about going because she wasn’t getting any award and she hadn’t been there long. Ms Marwick recalled she encouraged Julie to go and meet new people. They also discussed what Julie might wear to the function. Julie mentioned a long black skirt and nice shirt that went with it as an option. Julie seemed fine and her usual self during the phone call. At the end of the call they made arrangements to catch up in a few weeks.89

THE PARMELIA FUNCTION

67. The police investigation established Julie drove to the city in her Fiat sedan and parked in a Wilson carpark next door to the hotel. She commenced work at about 5.00 pm. Her shift was said to be uneventful, with Julie taking meals to ten rooms during the evening. Police have made inquiries with the persons listed as having received the meals Julie delivered and there is no suggestion of any of these people being involved in her disappearance.90

68. The Parmelia Hilton was hosting a staff function/awards presentation night that evening at Juliana’s nightclub, which was located on the ground floor within the hotel complex. The nightclub was closed to the general public on Sunday nights, which was why the staff function was able to be held there.91

69. One of Julie’s work colleagues, Consuelo (Connie) Harper, remembered changing in the female staff change room after finishing her shift early and Julie was also getting changed at the same time. Another female employee, Lilliana Colletti, was also there. Ms Harper was quite friendly with Julie and they had been out together a few times with other colleagues. She remembered Julie as a bubbly and friendly person. Their friendship was based around working together, so they didn’t talk about their private lives and Ms Harper didn’t know Julie’s family or friends.92

70. On this night, Ms Harper recalled Julie got changed out of her uniform into a black, high necked, long sleeve dress that had a gold button on the right shoulder. She thought Julie was also wearing black stockings and black shoes and holding a small wallet or purse. It was about 10.00 pm when they got changed. All three ladies then went to the function together.93

71. There were estimated to be approximately 180 guests at the function, the majority of whom were staff of the hotel or partners and friends of staff members. The function had commenced at 7.00 pm and awards were presented. Food and drinks were available and there was a DJ playing music.94

72. Upon entering Juliana’s, Julie bought both Ms Harper and herself a champagne. After handing Ms Harper her drink, Julie began talking to other people. While Ms Harper continued to drink the same glass of champagne, she noticed Julie ordered three more glasses of champagne and drank them all quickly.95 Julie was seen by other guests either talking with people, sitting at the bar having a drink or dancing on the dance floor.96

73. Towards the end of the function, Tadeusz Maciejewski introduced himself to Julie. They spoke for about 15 minutes before dancing together for about the same amount of time. Gregory Swiatek, a friend and flatmate of Mr Maciejewski, then joined them on the dance floor.97 I note that another work colleague expressed the opinion later that the two men were “scumbags”98 and he eventually got both of them sacked from the hotel because he didn’t like them and had reported them for inappropriate behaviour before they were dismissed. The behaviour appeared to relate to eating food intended for guests and generally shirking work and not following direction rather than anything suggestive of inappropriate behaviour towards female staff.99 On this night, they were both still hotel employees, the same as Julie, but it doesn’t appear she had met them before.

74. Shortly after midnight on Sunday, 20 June 1988, Ms Harper went looking for Julie. She found Julie talking to the two men, Mr Maciejewski and Mr Swiatek, on the dance floor. Julie introduced her to them and the two men invited them back to their house to have a drink and watch a movie. Ms Harper declined and said she wanted to go home. Julie said, “Alright, if you want to go, I’ll go too.”100 Ms Harper walked out of Juliana’s, leaving Julie still talking to the two men. Julie followed shortly afterwards and they met up in the ladies change room. Julie said to Ms Harper, “Do I have to go with them or not?” Ms Harper replied, “It’s up to you, but you had better go home. You are drunk.” Julie replied, “Alright, I’ll go home.”101

75. I note that when Ms Harper spoke to the police again much later, she didn’t recall this conversation, but did recall Julie pointing out a man and saying she had been invited to a party in Cottesloe with the man, but Ms Harper told Julie she was tired and wanted to go home.102

76. Either way, Ms Harper did recall that she and Julie left the nightclub together and collected their things from the ladies changeroom. Ms Harper recalled Julie had a big leather shoulder bag that was light tan in colour and she was carrying her uniform in a plastic bag. They walked out of the hotel through the rear staff entrance and walked to the nearby Wilson carpark. Ms Harper recalled that Julie still appeared drunk at that time. A number of other party guests were also leaving around the same time and spoke to Julie in the carpark.103

77. Ms Harper told a police officer in 1988 that as they reached the carpark, Julie told her that she was going to see a friend somewhere, but she wouldn’t tell her who it was she was going to see. Ms Harper said, “Come on , you tell me who.” Julie replied, “No, I can’t tell you it’s a secret. I can’t tell.”104 When asked about this conversation many years later, Ms Harper did not recall it.105 Detective Senior Constable Ronald Carey,106 who had a key role in the 1988 investigations and took the original statement from Ms Harper, recognised his handwriting that recorded that information, but he did not have an independent recollection of the circumstances in which Ms Harper provided that information to him. He could only infer that she provided the information to him in 1988 around the time she provided the rest of her statement, noting he spoke to her a number of times and sometimes people remember more information over time.107

78. The two women walked to their vehicles. Ms Harper’s car was parked in one row, and Julie’s grey car was parked in the row behind. They separated and Ms Harper heard Julie speak to a man and woman and wish them a goodnight. Ms Harper did not see them but heard their voices. Ms Harper then said goodbye to Julie as she got into her car. Julie was standing by her open passenger side door, bending into the car fiddling with something at the time, and did not reply. Ms Harper then drove away, while Julie was still standing at the passenger side of her car.108

79. Other employees of the Parmelia Hilton recalled seeing Julie back at the nightclub after this time. The police concluded that Julie re-entered the hotel complex for a short time and went back into Juliana’s nightclub. The function finished between 12.30 am and 1.00 am and Julie was one of the last four or five people to leave the function room. The doors to the nightclub were closed after Julie left. The Banqueting and Beverage Manager, John Comerford, recalled Julie leaving around 12.30 am walking out of the nightclub by herself. He went to the Wilson carpark shortly afterwards to collect his car and didn’t see Julie in the carpark.109 Julie said goodbye to another colleague, Kevin Williams, in the main lobby area of the hotel before walking out of the hotel via the main entrance and turning left onto Mill Street. It seems Julie then returned to the carpark, got into her car and drove out of the carpark.110

80. Another Parmelia Hilton employee, Geoffrey Pearce, left the nightclub function around midnight. He left the hotel and went to wait outside the Wilson Carpark for his girlfriend to collect him. Mr Pearce’s girlfriend had been working at the casino and was running late. Mr Pearce recalls he was standing under a tree while he waited as it was raining and he was trying to keep dry. He was watching the cars coming out of the Wilson’s carpark while he waited, and saw Julie drive out of the Wilson’s carpark. She wound down her window and asked him if he was alright, and Mr Pearce said, “I’m fine, waiting for my girlfriend.” 111 Mr Pearce remembered Julie stopped at the exit of the carpark, looked right and then drove off to the left, down Mounts Bay Road. He could not recall what car Julie was driving, but knew Julie as a work colleague and was positive it was Julie who stopped and spoke to him before driving off. 112 This appears to be the last known sighting of Julie Cutler.113

MISSING PERSON REPORT

81. At the time of her disappearance, Julie still lived at the unit in Stirling Street, Fremantle, with Fiona Marr. Fiona had seen Julie before she left for work on the Sunday but Julie had been gone when Fiona came home on the Sunday afternoon and she did not see her that night. Fiona noticed Julie’s car was not parked in the carport when Fiona left for work on the morning of Monday, 20 June 1988. Fiona wasn’t sure whether Julie had returned home during the night whilst she was sleeping, but there was nothing to suggest Julie had been home and gone out again, which Fiona thought was odd. Fiona went to work on the Monday as usual. Fiona couldn’t recall if she made any calls to locate Julie during the day, but she did recall that Julie was still not home when she returned from work. Fiona said she had a “creepy feeling that something wasn’t right”114 by that stage.115

82. Fiona gave evidence Julie was normally communicative about where she was, so her level of concern was increasing and she began to make enquiries as more time passed. Julie’s aunt, Ms Marwick, received a call from Fiona on the Monday asking if she had seen or heard from her as Julie had not come home from work on the Sunday. Fiona asked Ms Marwick if she thought she should report Julie missing to the police. Julie’s aunt suggested she ring Julie’s father first. Fiona did not have his number, so Ms Marwick offered to make the call.

83. By that time, Julie’s father, Roger Cutler, was living in Kalgoorlie.116 Mr Cutler apparently told Ms Marwick he would call Fiona. Mr Cutler spoke to Fiona and recalled that Fiona asked him if he thought she should call the police and he agreed. He said in his statement that at the time, he thought it was “more to teach her a lesson.”117 Mr Cutler explained at the inquest that this was simply because he didn’t think anything had actually happened to his daughter at that time, and he thought having the police check up on her would remind her that she needed to keep people informed. It was only when Julie’s car was found that he realised something was terribly wrong.118

84. Julie’s aunt had rung her mother, Julie’s grandmother, in York to make sure Julie hadn’t gone there for a visit. Her mother had not heard from Julie.119

85. Fiona had become increasingly concerned, so at 10.00 am on 21 June 1988 she filed a formal missing person report with the WA Police at Fremantle Police Station. Fiona said she gave the police as much information as she knew at the time. Julie was noted to have never gone missing before and all items of her property, such as bankcards and clothes, appeared to still be at her home, other than her car. Fiona did not have any idea what might have happened to Julie at that time, she was just concerned as she had not returned home, which was out of character.120

DISCOVERY OF JULIE’S CAR IN THE OCEAN

86. Mr John Mickle went down to Cottesloe Beach for a swim on the morning of Wednesday, 22 June 1988. He usually went swimming in the water directly opposite to the Cottesloe Life Saving Club’s boat shed. Mr Mickle arrived at the beach at about 10.30 am and went for a walk up the coast. After the walk, he returned to the boat shed and entered the water for a swim at about 11.45 am. He had his diving goggles on and was swimming about half way between the boat shed and the groyne that was south of the boat shed. When Mr Mickle reached a water depth of about six feet, he noticed a car upside down and half buried in the sand. He looked at the doors and they appeared to be jammed shut because of the sand. Mr Mickle left the water and approached a Cottesloe Council lifeguard, Mr Craig Fowler, on the beach. He told the lifeguard about the car in the water.

87. Mr Fowler had started work at the beach at 5.00 am that morning and during an early patrol of the beach that morning he recalled locating a brown car seat washed up against the wall of the groyne. The weather that day was fine and relatively calm, but it had been very windy and stormy the previous days and the water had been lapping up against the wall of the groyne. Mr Fowler recalled it had been too rough to swim and the water had been murky due to the stormy conditions.121

88. Mr Fowler’s colleague, Stephen Graybrook, also recalled that he had found a pair of women’s black high heeled shoes, a small pink woman’s handbag, some paperwork and a car battery washed up in the area between the pylon and the Groyne wall, possibly on the Monday morning. He noted it had been very stormy and it wasn’t unusual for items to wash up in such weather. Mr Graybrook recalled that he and Mr Fowler collected all the items and took them to the temporary rubbish depot, which was situated off Broome Street in Cottesloe. He later assisted police to recover those items from the rubbish depot, as they were easily identified. Mr Graybrook seemed to think all these events occurred on the one day, rather than some on Monday and some on Wednesday, so it’s not entirely clear when the items washed up.122

89. Mr Mickle had recalled that he took Mr Fowler to where the car was located in the water, but Mr Fowler’s colleague, Stephen Graybrook, recalled that Mr Fowler touched the car with his foot while they were both surfing and they recognised the smell of engine oil.123

90. Either way, Mr Fowler did locate the car on the Wednesday in the water. Mr Fowler could see the car was about 30 feet from the waterline, midway between the groyne and the Cottesloe Life Saving Club boat sheds in about six or seven feet of water. Mr Fowler went into the water on his paddleboard to have a look at the car. He noted it was very dirty in the water, so he couldn’t see much, but he could see the car fully submerged in the ocean, in a natural hollow between the two reefs. Mr Fowler returned to shore and then swam out to the car to take a closer look. He could see the car was on its roof with the engine facing out towards the ocean. He noted the car was damaged and the roof was caved in. It was also semi-submerged in the sand. He could see the windows were either down or smashed.124

91. Mr Fowler swam down to look inside the car through a window. He noted the inside of the car “was a real mess but there was nothing in the car”125 or at least nothing unusual. Mr Fowler later told police he did not recall seeing a concrete block in the car and did not remember ever hearing about one being found in the car.126 Mr Fowler took one of the registration plates off the back of the car and brought it to shore so he could provide the information to police.127

92. Another ranger telephoned the police and told them what they had found. The police asked them to tie a buoy to the car, so Mr Fowler swam back out to the car and tied a buoy to it, so it could be seen from the shore.128

93. At approximately 12.40 pm detectives were called to the beachfront adjacent to the Cottesloe Beach groyne after receiving a report that surfers had seen an upturned motor vehicle in the ocean. Police officers from other sections also attended.129

94. Senior Sergeant Christopher Ruck was stationed at the Water Police and was working as a Police Diver back in 1988. He recalled attending Cottesloe Beach with other officers from Water Police. Senior Constable Ruck and another officer, Constable Wayne Pettit, went out into the water approximately 70 metres north of the Cottesloe Groyne in front of the Cottesloe Surf Club Service Road. Senior Sergeant Ruck recalled that approximately 50 metres from shore he saw the undercarriage of the Fiat and on diving down, he could see the car was resting on its roof on a small reef in approximately two metres of water. The roof was crushed into the cabin. The visibility was poor and Senior Sergeant Ruck couldn’t see into the vehicle.130

95. Initially the police tow truck was brought in, but it became bogged, so arrangements were made to bring in a larger four-wheel drive truck and this was used to tow the car from the water.131 Senior Sergeant Ruck attached a tow line to the car and it was pulled into the shallow water by the tow truck driver, Clinton Hodge of Swan Towing. Once the car was in the shallows, a spare tyre surfaced from the car’s open boot. Senior Sergeant Ruck and Constable Pettit connected chains from the tow truck to the left side of the car’s undercarriage at that stage, and the tow truck driver then winched the car onto its wheels and onto the beach. Once on the beach, the car was examined and identified as a Fiat 124 sedan, light brown in colour. It was noted to have substantial damage to the body panels and the bonnet and roof had been torn from the chassis. Inside the cabin, the rear seat and carpet was missing. The car keys, however, were in the ignition, and attached to them was Julie’s house key.132 The tow truck driver delivered the Fiat to the Maylands Police Complex for further examination.133

96. It was noted in a later report that the damaged vehicle was found to be unoccupied and devoid of personal property. Inquiries revealed that Julie was the owner of the vehicle and she had been reported as a missing person. Due to the unusual circumstances of the discovery of the car and the fact the owner was missing, officers of the CIB Major Crime Squad were called in to assist with the investigation.134

THE SEARCH

97. Police conducted land, air and sea searches for several days after the discovery of Julie’s car, looking for any sign of her.135 Police divers searched the ocean floor as far as they could, but nothing was found.136 Water police in boats searched an area from North Mole in Fremantle to Hillarys up to 2.5 kilometres from shore. Mounted police patrolled the beach from North Mole up to an area as far they thought reasonable to the north. Cottesloe Council rangers in four wheel drives and police officers and volunteers on foot searched the coast from Scarborough to Fremantle. Some items of property were located, but when they were shown to Julie’s family and friends none were identified as belonging to Julie.137 Despite the intensive search efforts, no sign of Julie was found.

98. Julie’s father had come to Perth and stayed with her sister Nicole. They were hoping Julie would come home, but sadly, she never did.138 Julie’s father and sister later provided DNA samples to police to assist with comparing any unidentified remains found to Julie’s closest relatives, but no match has been found.

FORENSIC EXAMINATION OF JULIE’S CAR AND THE SCENE

99. Luke Marsland was a First Class Constable working as a Forensic Investigator in June 1988. He was asked many years later, as part of the Cold Case Investigation, whether he could recall any forensic action he took in relation to Julie’s disappearance. Constable Marsland located his old police notebook from the relevant period 26 March 1988 to 17 October 1988, which assisted him to identify the steps he had taken.

100. In his notebook, Constable Marsland had recorded that he took photographs of Julie’s Fiat at Cottesloe Beach when it was pulled from the ocean by the tow truck.139 Constable Marsland also attended Maylands Police Complex on 23 June 1988 to examine the Fiat along with two vehicle examiners and an officer from the Fingerprint Bureau. As a result of the examination, it was recorded that:140

• The ignition key was turned on;

• The lights were on;

• The gear was in neutral;

• The seat right forward was locked;

• The two rear doors were locked;

• The two front doors were unlocked;

• The driver’s door window was wound down;

• All the other windows were up;

• The driver’s door was open/ajar; and

• Located in the glove box was the vehicle licence papers with a handwritten note on the back – ‘Mike 114 Walpole St up Albany Highway’.

It was established that this was Julie’s handwriting and was an address where two of her friends lived. There was, however, no ‘Mike’ known to live at the address.141 Detective Carey gave evidence it was considered to have no relevance to Julie’s disappearance.142

101. A more detailed report of the examination of the Fiat, prepared by Constable Marsland, indicated that the body work of the Fiat was in an extremely battered condition. The damage was consistent with the car being pounded by surf over a period of time. All window glass and front and rear windscreens had been smashed, with the exception of the left front door quarter glass window. The driver’s door was unlocked and jammed open three inches. The window had been wound right down and the quarter glass window was closed and locked. The front left hand door was closed but unlocked with the window wound up. Both rear doors were closed and locked with the windows wound up. The boot lid was open and locked and the spare tyre and jack were inside. The ignition key was in the on position, indicating the motor would have been running, the gear shift was in neutral (but could have been knocked into that position as it was loose) and the handbrake was in the off position. The headlights and park lights were switched on. The driver’s front bucket seat was locked in the full forward position and it had a two-piece seat cover on it from which hairs were recovered. The rear seat was found by the ranger, Mr Fowler, loose in the surf.143

102. After the examination, Constable Marsland submitted property items related to the matter to the Forensic Branch Exhibits Officer. These items were recorded into the Forensic Branch Exhibit Register, as follows:144

• Two wine glasses and tea towel;

• One easybank card;

• RAC membership card and folder with pamphlets,

• motor vehicle licence for the Fiat with the handwritten note on the back,

• BP service ariel key,

• Two cigarette butts, three paperbook matches burnt;

• Broken plastic fan blade;

• Top half seat cover;

• Bottom half seat cover; and

• Assorted hairs from driver’s seat cover.

103. A manager from the Parmelia Hilton was shown the wine glasses and tea towel uncovered from Julie’s car some years later. He thought the glasses were of a similar style to glasses used at the hotel for champagne service back at that time but could not recall what kind of tea towels were generally used in the hotel in 1988.145

104. Constable Marsland later told the Cold Case Homicide investigators that he recalled helping to search Cottesloe Beach for any items that may have washed up on the shore that belonged to Julie and he did not recall locating any such items. He believes that if anything was located at that time, he would have taken photographs of the property and ensured the items were recorded at the Forensics Branch.

105. The items listed above, other than seat covers and associated hairs, were found in the ash tray and glove box of the vehicle. The ash tray contained the burnt matchbooks and cigarette butts. The glove box had two clear glass champagne flutes wrapped in a green and white striped tea towel, along with the bank card and RAC car, vehicle licence paper for the Fiat in Julie’s name and a BP service sheet.146

106. Other than the hairs in the car seat, no physical evidence such as clothing, bags, shoes, human tissue or blood were located in the vehicle.147

107. Constable Marsland also recorded in his notebook that on 23 June 1988 at 4.30 pm he collected approximately 10 to 12 pieces of flesh from the Water Police and delivered them to a forensic pathologist, Dr Hilton, at the State Mortuary and another sample to Frank Vlatko-Rule at Forensic Pathology for testing. Dr Hilton advised police that the substances were not human.148

108. Constable Marsland told police in 2018 that he did not recall seeing a battery belonging to the Fiat washing up on the beach (the battery was noted to be missing during the vehicle examination)149 and he did not recall seeing a car seat from the car washed upon the beach. He did recall that the bonnet of the Fiat had been located separate from the car. He believed it became detached while the car was being retrieved from the ocean by the tow truck and was placed on the tow truck along with the car to be taken to Maylands Police Complex. Constable Marsland did not recall any large rock or piece of concrete being located in the Fiat.150 In addition, Constable Marsland did not recall taking away from the Fiat any indicator globes and stated the policy was that any globes were tested in situ.151

109. Constable Marsland’s report, prepared when he was a First Class Constable and directed to his superior, Sergeant Thomas, indicated that his examination of the rock groyne at Cottesloe Beach revealed no evidence that the car had been driven off it at any point and it appeared quite unlikely that a vehicle could be launched off the top of the groyne over the large rocks, which slope down to the ocean. Constable Marsland suggested that a more feasible way the vehicle could have got into the ocean was for it to have been driven down the service road at the change room building and launched off the flat concrete edged road into the water at high tide. Scrape marks and a chipped corner of the concrete edge were evident at this location. However, although the broken away section looked fresh, it could not be determined how long ago the damage may have occurred and it was noted no concrete debris could be located on the sand around this point. Constable Marsland commented that there was no other evidence in this area to indicate the vehicle entered the water at this point, but it was “the most logical.”152 However, an examination of the underside of the Fiat revealed no scrape marks consistent with the scrape marks and chipped concrete on the Cottesloe Beach service road. Minor scratches under the rear of the vehicle were noted, but they were consistent with the chains used to retrieve the vehicle by winch from the surf.153

110. Detective Carey was working in the Major Crime Squad in June 1988 and he attended Cottesloe Beach the day Julie’s car was found as part of a team of investigators put together by Detective Senior Sergeant Katich. Detective Carey gave evidence at the inquest that the police believed with some certainty that Julie’s car entered the ocean the night she went missing. Detective Carey gave evidence the damage to Julie’s car was felt to have been caused by the car rocking back and forward on its roof in heavy seas for a couple of days, causing it eventually to be crushed. The detectives investigating the case also believed with some degree of certainty her car entered the water off the side road next to the historic Cottesloe beach building. The night she disappeared was a very stormy night and the tide was very high, with waves and the ocean coming over the limestone retaining wall, which would have allowed the car to be washed into the ocean. The lack of frontal damage ruled out entry to the water from the groyne.154

111. I note at this stage, there was never any evidence of a lump of concrete being found in Julie’s care. Julie’s father recalled being asked sometime later by a person he believed was a female police officer whether a concrete block had been found in the car by a police diver. He was surprised by the question as it was not information he had ever been told before and he thought it unlikely, given the car was found upside down with no roof.155 Detective Carey confirmed at the inquest that there were no concrete blocks found in the recovered Fiat of any size.156

INITIAL POLICE INVESTIGATION

112. On 23 June 1988 at about 4.10 pm, detectives spoke to the two men who had been seen talking to Julie on the dance floor at the nightclub and had invited her back to their flat, Mr Swiatek and Mr Maciejewski. Detectives thoroughly searched their flat and vehicle in Glendalough that day. The search had a negative result. Both men were interviewed and readily volunteered the information that they had been speaking with Julie and Connie Harper shortly before the conclusion of the Parmelia staff function, at approximately 12.15 am on Monday, 20 June 1988, but neither man could offer any more information that could be of assistance.157

113. Police officers interviewed various other Parmelia Hilton staff members who came forward to provide what information they could, but nothing of value was obtained.158

114. A gentleman by the name of Mokhtar Khir was working as the General Manager of the Merlin Hotel and investigations suggested that Julie had possibly been in a relationship with him at the time she disappeared. Mr Mokhtar was spoken to by police on 24 June 1988 and he said he had met Julie two weeks prior to her disappearance at the disco at the Merlin Hotel and he later escorted her to the casino, where they were together until about 4.00 am. They made plans to meet several days later but Julie did not keep the appointment. Mr Mokhtar told police he last spoke to Julie on 16 June 1988 when he rang her at the hotel. He invited her out to dinner, which she declined. Mr Mokhtar was married at the time and denied any sexual involvement with Julie. Detective Carey interviewed Mr Mokhtar and believed he had associated with Julie but there was no evidence to suggest he had any connection to Julie’s disappearance.159

115. Police officers spoke to Leona Rich who lived in Victoria at the time and was in regular communication with Julie. Ms Rich advised police she had spoken to Julie on the telephone on the Wednesday, about a week before she disappeared and at that time Julie was very upset about her love life and spoke of an Asian gentleman at work. Another friend who lived in Victoria was spoken to and he told police he had spoken to Julie a couple of weeks before her disappearance and she had seemed okay at that time.160

116. At the conclusion of the initial police investigation into Julie’s disappearance in December 1988, it was noted by Detective Carey that Julie’s body had not been found despite a land, air and sea search of Cottesloe Beach and her disappearance remained “unresolved.”161 After speaking to a number of persons of interest, the 1988 investigation did not identify any formal suspects in relation to Julie’s disappearance. The file remained open pending any further new information to prompt further lines of investigation.162 Detective Carey, who had carriage of the investigation for some time, left Major Crime in 1993 and the investigation passed over to other detectives from that time.163

117. Detective Carey gave evidence at the inquest that the police officers involved in the initial investigation were very disappointed that they couldn’t resolve the case and find the reason why Julie had disappeared. He had been involved in approximately 20 death-related inquiries while working at Major Crime Squad and Julie’s case was one of only two that remained unresolved, despite being thoroughly investigated. Detective Carey had met with Roger Cutler multiple times, along with Detective Katich, and had found it very distressing that they could not offer Mr Cutler and the rest of Julie’s family any answers. Detective Carey noted it was a very unusual case and he still lives in hope that one day someone will come forward and provide the key information that will help solve the case.164

118. Although he had no further personal involvement in the investigation after 1993, Detective Carey has had many years to consider the matter and was made aware of many of the more recent developments. At the inquest, Detective Carey said he believed Julie’s car must have gone into the water before the sun came up on the Monday morning as there was always an inspector at the beach from 5.00 am and no one saw the car enter the water. If it had gone in any later, it would not have made it into the water as the water did not come up to the wall any other night. Further, he was aware the back seat from her car (or possibly the battery) washed up on the Monday morning and was found by one of the Cottesloe beach inspectors.165

119. Detective Carey noted that the seat/battery washed up to shore but not Julie’s body or her handbag or the plastic bag containing her uniform. While Detective Carey accepted that the oceanographers Detective Katich consulted as part of the initial investigation indicated there was nothing certain about how different objects will behave in the sea, and items could have been washed out to sea rather than on to the shore like the seat, the obvious other alternative is that Julie was not in the car when it went into the ocean. Testing at the time suggested the car could have entered the water while being driven by someone or while unoccupied, given it could have simply rolled down the hill and gathered up enough speed to launch over the wall. Detective Carey believes if Julie was not in the car when it entered the ocean, this would support the proposition that someone else was involved in her disappearance. However, Detective Carey also noted that the car went into the water at Julie’s favourite beach, so the particular location raises its own questions.166

POLICE REVIEW AUGUST 1998 – OPERATION DAMOCLES

120. In August 1998 a review of Julie’s file was commenced by the Macro Task Force and given the name Operation Damocles. It had been noted that there were similarities between Julie and the disappearances of Sarah Spiers, Jane Rimmer and Ciara Glennon. Although Julie disappeared some eight or nine years before the other young women, it was noted that they all lived or grew up in the same area, had an association with Iona Presentation College, were of similar age when they went missing and were of similar descriptions.167

121. In addition, it had been ascertained that Mr Edwards had been studying at WAIT at the same time as Julie, with some overlap as they were both studying psychology. However, they did not appear to have been in the same classes/tutorials and there was no established contact between them.168

122. The timing of Julie’s disappearance was much earlier than the later known abductions. Mr Edwards would only have been 19 years of age at the time Julie went missing, and his documented behaviours at that time were more focussed around a series of burglaries and other disturbing activities in the Huntingdale area rather than the western suburbs, although that does not mean he was not active in Claremont at that early stage. The manner in which Julie disappeared was also considered to be very different to the later known events.169

123. Ten years after Julie’s disappearance, police officers received some information about a short film directed by Peter Grant in 1986 called ‘Nocturnes’ that might have relevance to Julie’s disappearance. Mr Grant had been a student at WAIT at the same time as Julie and he made the film between July and September 1986, a couple of years before her disappearance. The film was about a male and female who both decide to commit suicide. The female commits suicide in a bath and the male commits suicide by driving his vehicle off a groyne into the ocean at night. The film itself does not make it clear that the car is driven off the Cottesloe groyne, although that is in fact where it was filmed. Peter Docker, who Julie had been seeing at the time and was described by some as her boyfriend, was the main actor and played the part of the male who ultimately drives his car off the groyne into the ocean, although Mr Docker did not film that actual scene.170

124. On Tuesday, 10 November 1998, two officers who were involved in Operation Damocles, Detective1/C Selby and First Class Constable Kinsella, went to the address of Peter Grant to talk to him about the film. Mr Grant told the police that he had thought it funny when he had heard a couple of years later that a car had been found in the ocean off Cottesloe Groyne, but had not thought more about it. He had not realised it was Julie Cutler’s vehicle and he did not know Julie was a missing person, so it had not occurred to him to contact police at the time and advise them of his movie and its similarity to what had occurred in 1988. Mr Grant told police he knew Julie through her association with Mr Docker, although he said he did not know her well and she did not play a role in the short film 171